Beethoven: man, composer and revolutionary - Part one

Friday, 19 May 2006

"Beethoven is the friend and contemporary of the French Revolution, and he remained faithful to it even when, during the Jacobin dictatorship, humanitarians with weak nerves of the Schiller type turned from it, preferring to destroy tyrants on the theatrical stage with the help of cardboard swords. Beethoven, that plebeian genius, who proudly turned his back on emperors, princes and magnates - that is the Beethoven we love for his unassailable optimism, his virile sadness, for the inspired pathos of his struggle, and for his iron will which enabled him to seize destiny by the throat."

Igor Stravinsky

If any composer deserves the name of revolutionary it is Beethoven. The word revolution derives historically from the discoveries of Copernicus, who established that the earth revolves around the sun, and thus transformed the way we look at the universe and our place in it. Similarly, Beethoven carried through what was probably the greatest single revolution in modern music. His output was vast, including nine symphonies, five piano concertos and others for violin, string quartets, piano sonatas, songs and one opera. He changed the way music was composed and listened to. Right to the end, he never ceased pushing music to its limits.

If any composer deserves the name of revolutionary it is Beethoven. The word revolution derives historically from the discoveries of Copernicus, who established that the earth revolves around the sun, and thus transformed the way we look at the universe and our place in it. Similarly, Beethoven carried through what was probably the greatest single revolution in modern music. His output was vast, including nine symphonies, five piano concertos and others for violin, string quartets, piano sonatas, songs and one opera. He changed the way music was composed and listened to. Right to the end, he never ceased pushing music to its limits.

After Beethoven it was impossible to go back to the old days when music was regarded as a soporific for wealthy patrons who could doze through a symphony and then go home quietly to bed. After Beethoven, one no longer returned from a concert humming pleasant tunes. This is music that does not calm, but shocks and disturbs. it is music that makes you think and feel.

Early years

Marx pointed out that the difference between France and Germany is that, whereas the French actually made revolutions, the Germans merely speculated about them. Philosophical idealism flourished in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries for the same reason. In England the bourgeoisie was effecting a great world-historical revolution in production, while across the English Channel, the French were carrying out an equally great revolution in politics. In backward Germany, where social relations lagged behind France and England, the only revolution was a revolution in men's minds. Kant, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel argued about the nature of the world and ideas, while other people in other lands actually set about revolutionising the world and the minds of men and women.

The Sturm und Drang movement was an expression of this typically German phenomenon. Goethe was influenced by German idealist philosophy, especially Kant. Here we can detect the echoes of the French revolution, but they are distant and indistinct, and they are strictly confined to the abstract world of poetry, music and philosophy. The Sturm und Drang movement in Germany reflected the revolutionary nature of the epoch at the end of the 18th century. It was a period of enormous intellectual ferment. The French philosophes anticipated the revolutionary events of 1789 by their assault on the ideology of the old regime. As Engels put it in the Anti-Duhring: “The great men, who in France prepared men's minds for the coming revolution, were themselves extreme revolutionists. They recognised no external authority of any kind whatever. Religion, natural science, society, political institutions — everything was subjected to the most unsparing criticism; everything must justify its existence before the judgment-seat of reason or give up existence. Reason became the sole measure of everything. It was the time when, as Hegel says, the world stood upon its head; first in the sense that the human head, and the principles arrived at by its thought, claimed to be the basis of all human action and association; but by and by, also, in the wider sense that the reality which was in contradiction to these principles had, in fact, to be turned upside down.”

| |

| Bonn in the 18th century |

The impact of this pre-revolutionary ferment in France made itself felt far beyond the borders of that country, in Germany, England, and even Russia. In literature, gradually the old courtly forms were being dissolved. This found its reflection in the poetry of Wolfgang Goethe – the greatest poet Germany has produced. His great masterpiece Faust is shot through with a dialectical spirit. Mephistophiles is the living spirit of negation that penetrates everything. This revolutionary spirit found an echo in the later works of Mozart, notably in Don Giovanni, which among other things contains a stirring chorus with the words: “Long live Liberty!” But it is only with Beethoven that the spirit of the French Revolution finds its true expression in music.

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn on November 16, 1770, the son of a musician from a family of Flemish origin. His father, Johann, was employed by the court of the Archbishop-elector. He was by all accounts a harsh, brutal and dissolute man. His mother, Maria Magdalena, bore her martyrdom with silent resignation. Beethoven’s early years were not happy. This probably explains his introverted and somewhat surly character as well as his rebellious spirit.

Beethoven’s early education was at best patchy. He left school at the age of eleven. The first person to realise the youngster’s enormous potential was the court organist, Gottlob Neffe, who introduced him to the works of Bach, especially the Well-Tempered Klavier.

Noting his son’s precocious talent, Johann tried to turn him into a child prodigy – a new Mozart. At the age of five he was exhibited at a public concert. But Johann was doomed to disappointment: Ludwig was no childhood Mozart. Surprisingly, he had no natural disposition for music and had to be pushed. So his father sent him to several teachers to drum music into his head.

Beethoven in Vienna

At this time Bonn, the capital of the Electorate of Cologne, was a sleepy provincial backwater. In order to advance, the young musician had to go to study music in Vienna. The family was not rich, but in 1787 the young Beethoven was sent to the capital by the Archbishop. It was here that he met Mozart, who was impressed by him. Later one of his teachers was Haydn. But after only two months he had to return to Bonn, where his mother was seriously ill. She died shortly afterwards. This was the first of many personal and family tragedies that dogged Beethoven all his life. In 1792, the year in which Louis XVI was beheaded, Beethoven finally moved from Bonn to Vienna, where he lived till he died.

|

| Vienna in Beethoven's time |

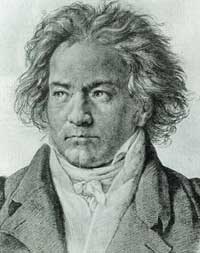

The portraits that have come down to us show a brooding, sombre young man with an expression that conveys a sense of inner tension and a passionate nature. Physically he was not handsome: a large head and Roman nose, a pock-marked face and thick, bushy hair that never seemed to be combed. His dark complexion earned him the nickname “the Spaniard”. Short, stocky and rather clumsy, he had the bearing and manners of a plebeian – a fact that could not be disguised by the elegant clothes he wore as a young man.

This born rebel turned up in aristocratic and fastidious Vienna, unkempt, ill-dressed and ill-humoured, with none of the polite airs and graces that might have been expected of him. Like every other composer in those times, Beethoven was obliged to rely on grants and commissions from wealthy and aristocratic patrons. But he was never owned by them. He was not a musical courtier, as Haydn was at the court of the Esternazy family. What they thought of this strange man is not known. But the greatness of his music ensured him of commissions and therefore a livelihood.

He must have felt completely out of place. He despised convention and orthodoxy. He was not in the least interested in his appearance or surroundings. Beethoven was a man who lived and breathed for his music and was unconcerned with worldly comforts. His personal life was chaotic and unsettled, and could be described as Bohemian. He lived in the utmost squalor. His house was always a mess, with bits of food lying around, and even unemptied chamber pots.

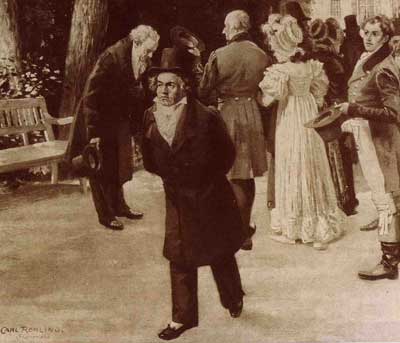

His attitude to the princes and nobles who paid him was conveyed in a famous painting. The composer is shown in the course of a stroll with the poet Goethe, the Archduchess Rudolph and the Empress. While Goethe respectfully gave way to the royal pair, politely removing his hat, Beethoven completely ignored them and continued walking without even acknowledging the greetings of the imperial family. This painting contains the whole spirit of the man, a fearless, revolutionary, uncompromising spirit. Suffocating in the bourgeois atmosphere of Vienna he wrote a despairing comment: “As long as the Austrians have their brown beer and little sausages, they will never revolt.” [1]

A revolutionary epoch

The world into which Beethoven was born was a world in turmoil, a world in transition, a world of wars, revolution and counter-revolution: a world like our own world. In 1776, the American colonists succeeded in winning their freedom through a revolution which took the form of a war of national liberation against Britain. This was the first act in a great historical drama.

The American Revolution proclaimed the ideals of individual freedom that were derived from the French Enlightenment. Just over a decade later, the ideas of the Rights of Man returned to France in an even more explosive manner. The storming of the Bastille in July 1789 marked a decisive turning point in world history.

In its period of ascent the French Revolution swept away all the accumulated rubbish of feudalism, brought an entire nation to its feet and confronted the whole of Europe with courage and determination. The liberating spirit of the Revolution in France swept like wildfire through Europe. Such a period demanded new art forms and new ways of expression. This was achieved in the music of Beethoven, which expresses the spirit of the age better than anything else.

|

| Revolutionary France |

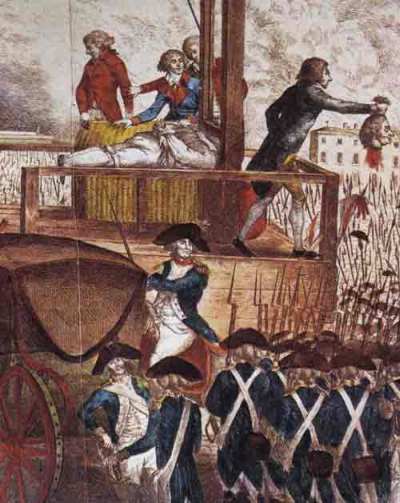

In 1793 King Louis of France was executed by the Jacobins. A wave of shock and fear swept through all the courts of Europe. Attitudes towards revolutionary France hardened. Those "liberals" who had initially greeted the Revolution with enthusiasm, now slunk away into the corner of reaction. The antagonism of the propertied classes to France was voiced by Edmund Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Everywhere the supporters of the revolution were regarded with suspicion and persecuted. It was no longer safe to be a friend of the French Revolution.

These were stormy times. The revolutionary armies of the young French republic defeated the armies of feudal-monarchist Europe and were counter-attacking all along the line. The young composer was from the beginning an ardent admirer of the French revolution, and was appalled at the fact that Austria was the leading force in the counter-revolutionary coalition against France. The capital of the Empire was infected by a mood of terror. The air was thick with suspicion; spies were ever-present and free expression was stifled by censorship. But what could not be expressed by the written word could find an expression in great music.

His studies with Haydn did not go very well. He was already developing original ideas about music, which did not go down well with the old man, firmly wedded to the old courtly-aristocratic style of classical music. It was a clash of the old with the new. The young composer was making a name for himself as a pianist. His style was violent, like the age that produced it. It is said that he hit the keys so hard he broke the strings. He was beginning to be recognised as a new and original composer. He took Vienna by storm. He was a success.

Life can play the cruellest tricks on men and women. In Beethoven's case, fate prepared a particularly cruel destiny. In 1796-7 Beethoven fell ill – possibly with a type of meningitis – which affected his hearing. He was 28 years old, and at the peak of his fame. And he was losing his hearing. About 1800 he experienced the first signs of deafness. Although he did not become completely deaf till his last years, the awareness of his deteriorating condition must have been a terrible torture. He became depressed and even suicidal. He wrote of his inner torment, and how only his music held him back from taking his own life. This experience of intense suffering, and the struggle to overcome it, suffuses his music and imbues it with a deeply human spirit.

|

| The young Beethoven |

His personal life was never happy. He had the habit of falling in love with the daughters (and wives) of his wealthy patrons – which always ended badly, with new fits of depression. After one such spell of depression he wrote: “Art, and only art, has saved me! It seems to me impossible to leave this world without having given everything I have felt germinating within me.”

At the beginning of 1801 he passed through a severe personal crisis. According to the Heiligenstadt Testament, he was on the verge of suicide. Having recovered from his depression, Beethoven threw himself with renewed vigour into the work of musical creation. A lesser man would have been destroyed by these blows. But Beethoven turned his deafness – a crippling disability for anyone, but a catastrophe for a composer – to an advantage. His inner ear provided him with all that was necessary to compose great music. In the very year of his most devastating crisis (1802) he composed his great Eroica symphony.

The dialectic of the sonata

The dynamics of Beethoven's music were entirely new. Earlier composers wrote quiet parts and loud parts. But the two were kept completely separate. In Beethoven, on the contrary, we pass rapidly from one to another. This music contains an inner tension, an unresolved contradiction which urgently demands resolution. It is the music of struggle.

The sonata form is a way of elaborating and structuring musical matter. It is based on a dynamic vision of musical form and is dialectical in essence. The music develops through a series of opposing elements. By the end of the 18th century the sonata form dominated much of the music composed. Although it is not new, the sonata form was developed and consolidated by Haydn and Mozart. But in the compositions of the 18th century we have only the bare potential of the sonata form, not its true content.

In part (but only in part) this is a question of technique. The form that Beethoven used was not new, but the way in which he used it was. The sonata form begins with a quick first movement, followed by a slower second movement, a third movement which is merrier in character (originally a minuet, later a scherzo, which literally means a joke), and ending, as it began, with a fast movement.

Basically, the sonata form is based on the following line of development: A-B-A. It returns to the beginning, but on a higher level. This is a purely dialectical concept: movement through contradiction, the negation of the negation. It is a kind of musical syllogism: exposition-development-recapitulation, or expressed in other terms: thesis-antithesis-synthesis.

This kind of development is present in each of the movements. But there is also an overall development in which there are conflicting themes which are finally reconciled in a "happy ending". In the final coda we return to the initial key, creating the sensation of a triumphal apotheosis.

This form contains the germ of a profound idea, and has the potential for serious development. It can also be expressed by a wide range of instrumental combinations: piano solo, piano and violin, string quartet, symphony. The success of the sonata form was helped by the invention of a new musical instrument: the pianoforte. This was able to express the full dynamic of romanticism, whereas the organ and harpsichord were restricted to play music written according to the principles of polyphony and counterpoint.

The development of the sonata form was already far advanced in the late 18th century. It reached its high point in the symphonies of Mozart and Haydn, and in one sense it could be argued that the symphonies of Beethoven are only a continuation of this tradition. But in reality, the formal identity conceals a fundamental difference.

In its origins, the form of the sonata predominated over its real content. The classical composers of the 18th century were mainly concerned with getting the form right (though Mozart is an exception). But with Beethoven, the real content of the sonata form finally emerges. His symphonies create an overwhelming sense of the process of struggle and development through contradictions. Here we have the most sublime example of the dialectical unity of form and content. This is the secret of all great art. Such heights have rarely been reached in the history of music.

Inner conflict

The symphonies of Beethoven represent a fundamental break with the past. If the forms are superficially similar, the content and spirit of the music is radically different. With Beethoven - and the Romantics who followed in his footsteps - what is important is not the forms in themselves, the formal symmetry and inner equilibrium, but the content. Indeed, the equilibrium is frequently disturbed in Beethoven. There are many dissonances, reflecting inner conflict.

In 1800 he wrote his first symphony, a work that still has its roots in the soil of Haydn. It is a sunny work, quite free from the spirit of conflict and struggle that characterises his later works. It really gives one no idea of what was to come. The Pathetique piano sonata (opus 13) is altogether different. It is quite unlike the piano sonatas of Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven was influenced by Schiller's theory of tragedy and tragic art, which he saw not just as human suffering, but above all as a struggle to resist suffering, to fight against it.

The message is clearly expressed in the first movement, which opens with complex and dissonant sounds (listen here). These mysterious chords soon give way to a central agitated passage which suggests this resistance to suffering. This inner conflict plays a key role in Beethoven's music and gives it a character completely different to that of 18th century music. It is the voice of a new epoch: a thunderous voice that demands to be heard.

The question that must be posed is: how do we explain this striking difference? The short and easy answer is that this musical revolution is the product of the mind of a genius. That is correct. Probably Beethoven was the greatest musical genius of all time. But it is an answer that really answers nothing. Why did this entirely new musical language emerge precisely at this moment and not 100 years earlier? Why did it not occur to Mozart, Haydn, or, for that matter, to Bach?

The sound world of Beethoven is not one composed of beautiful sounds, as was the music of Mozart and Haydn. It does not flatter the ear or send the listener away tapping his feet and whistling a pleasant tune. It is a rugged sound, a musical explosion, a musical revolution that accurately conveys the spirit of the times. Here there is not only variety but conflict. Beethoven frequently uses the direction sforzando – which signifies attack. This is violent music, full of movement, rapidly shifting moods, conflict, contradiction.

With Beethoven the sonate form advances to a qualitatively higher level. He transformed it from a mere form to a powerful and at the same time intimate expression of his innermost feelings. In some of his piano compositions he wrote the instruction: "sonata, quasi una fantasia", indicating that he was looking for absolute freedom of expression through the medium of the sonata. Here the dimension of the sonate is greatly expanded in comparison to its classical form. The tempi are more flexible, and even change place. Above all, the finale is no longer merely a recapitulation, but a real development and culmination of all that has gone before.

When applied to his symphonies the sonata form as developed by Beethoven reaches an unheard-of level of sublimity and power. The virile energy that propels his fifth and third symphonies is sufficient proof of this. This is not music for easy listening or entertainment. It is music that is designed to move, to shock and to inspire to action. It is the voice of rebellion cast in music.

This is no accident, for Beethoven’s revolution in music echoed a revolution in real life. Beethoven was a child of his age – the age of the French Revolution. He wrote most of his greatest work in the midst of revolution, and the spirit of revolution impregnates every note of it. It is utterly impossible to understand him outside this context.

Beethoven boldly swept aside all existing musical conventions, just as the French revolution cleaned out the Augean stables of the feudal past. His was a new kind of music, music that opened many doors for future composers, just as the French revolution opened the door to a new democratic society.

The inner secret of Beethoven’s music is the most intense conflict. It is a conflict that rages in most of his music and reaches its most impressive heights in his last seven symphonies, beginning with the Third symphony, known as the Eroica. This was the real turning-point in the musical evolution of Beethoven and also of the history of music in general. And the roots of this revolution in music must be found outside of music, in society and history.

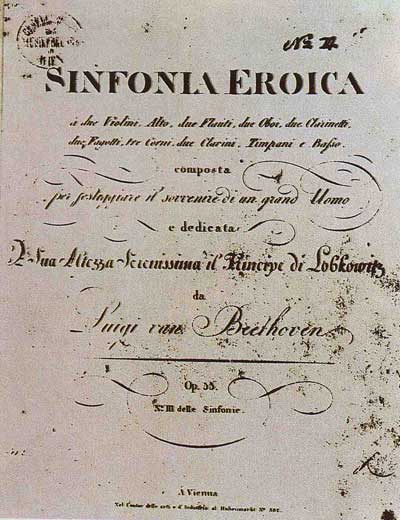

The Eroica symphony

A decisive turning-point both in Beethoven's life and in the evolution of western music was the compsition of his third symphony (the Eroica). Up till now, the musical language of the first and second symphonies did not depart substantially from the sound world of Mozart and Haydn. But from the very first notes of the Eroica we enter an entirely different world. The music has a political sub-text, the origin of which is well known.

Beethoven was a musician, not a politician, and his knowledge of events in France was necessarily confused and incomplete, but his revolutionary instincts were unfailing and in the end always led him to the correct conclusions. He had heard reports of the rise of a young officer in the revolutionary army called Bonaparte. Like many others, he formed the impression that Napoleon was the continuer of the revolution and defender of the rights of man. He therefore planned to dedicate his new symphony to Bonaparte.

This was an error, but quite understandable. It was the same error that many people committed when they assumed that Stalin was the real heir of Lenin and the defender of the ideals of the October revolution. But slowly it became clear that his hero was departing from the ideals of the Revolution and consolidating a regime that aped some of the worst features of the old despotism.

In 1799, Bonaparte's coup signified the definitive end of the period of revolutionary ascent. In August of 1802 Napoleon secured the consulate for life, with power to name his successor. An obsequious senate begged him to re-introduce hereditary rule “to defend public liberty and maintain equality”. Thus, in the name of “liberty” and “equality” the French people were invited to place their head in a noose.

It is always the way with usurpers in every period in history. The emperor Augustus maintained the outward forms of the Roman Republic and publicly feigned a hypocritical deference to the Senate, while systematically subverting the republican constitution. Not long afterwards, his successor Caligula made his prize horse a senator, which was a far more realistic appraisal of the situation.

Stalin, the leader of the political counter-revolution in Russia, proclaimed himself the faithful disciple of Lenin while trampling all the traditions of Leninism underfoot. Gradually the norms of proletarian soviet democracy and egalitarianism were replaced by inequality, bureaucratic and totalitarian rule. In the army, all the old rank and privileges abolished by the October revolution were reintroduced. The virtues of the Family were exalted. Eventually, Stalin even discovered a role for the Orthodox Church, as a faithful servant of his regime. In all this, he was only treading a road that had already been traversed by Napoleon Bonaparte, the gravedigger of the French Revolution.

In order to find some kind of sanction and respectability for his dictatorship, Napoleon began to copy all the outward forms of the old regime: aristocratic titles, splendid uniforms, rank and, of course, religion. The French revolution had practically wiped out the Catholic Church. The mass of the people, except in the most backward areas like the Vendee, hated the Church, which they correctly identified with the rule of the old oppressors. Now Napoleon attempted to enlist the support of the Church for his regime, and signed a Concordat with the Pope.

From afar, Beethoven followed the developments in France with growing alarm and despondency. Already by 1802 Beethoven’s opinion of Napoleon was beginning to change. In a letter to a friend written in that year, he wrote indignantly: “Everything is trying to slide back into the old rut after Napoleon signed the Concordat with the Pope.”

But far worse was to come. On May 18 1804 Napoleon became Emperor of the French. The coronation ceremony took place at the cathedral of Notre Dame on December 2nd. As the Pope poured holy oil over the head of the usurper, all traces of the old Republican constitution were washed away. In place of the old austere Republican simplicity all the ostentatious splendour of the old monarchy reappeared to mock the memory of the Revolution for which so many brave men and women had sacrificed their lives.

When Beethoven received news of these events he was beside himself with rage. He angrily crossed out his dedication to Napoleon in the score of his new symphony. The manuscript still exists, and we can see that he attacked the page with such violence that it has a hole torn through it. He then dedicated the symphony to an anonymous hero of the revolution: the Eroica symphony was born.

Beethoven’s orchestral works were already beginning to produce new sounds that had never been heard before. They shocked the Viennese public, used to the genteel tunes of Haydn and Mozart. Yet Beethoven’s first two symphonies, though very fine, still look back to the relaxed, easy-going aristocratic world of the 18th century, the world as it was before it was shattered in 1789. The Eroica represents a tremendous breakthrough, a great leap forward for music, a real revolution. Sounds like these had never been heard before. The unfortunate musicians who had to play this for the first time must have been shocked and completely bewildered.

Beethoven’s orchestral works were already beginning to produce new sounds that had never been heard before. They shocked the Viennese public, used to the genteel tunes of Haydn and Mozart. Yet Beethoven’s first two symphonies, though very fine, still look back to the relaxed, easy-going aristocratic world of the 18th century, the world as it was before it was shattered in 1789. The Eroica represents a tremendous breakthrough, a great leap forward for music, a real revolution. Sounds like these had never been heard before. The unfortunate musicians who had to play this for the first time must have been shocked and completely bewildered.

The Eroica caused a sensation. Up till then, a symphony was supposed to last at most half an hour. The first movement of the Eroica lasted as long as an entire sypmphony of the 18th century. And it was a work with a message: a work with something to say. The dissonances and violence of the first movement are clearly a call to struggle. That this means a revolutionary struggle is clear from the original dedication.

Trotsky once observed that revolutions are voluble affairs. The French Revolution was characterised by its oratory. Here were truly great mass orators: Danton, Saint-Just, Robespierre, and even Mirabeau before them. When these men spoke, they did not just address an audience: they were speaking to posterity, to history. Hence the rhetorical character of their speeches. They did not speak, they declaimed. Their speeches would begin with a striking phrase, which would immediately present a central theme which would then be developed in different ways, before making an emphatic re-appearance at the end.

It is just the same with the Eroica symphony. It does not speak, it declaims. The first movement of this symphony opens with two dissonant chords that resemble a man striking his fist on a table, demanding our attention, just like an impassioned orator in a revolutionary assembly. Beethoven then launches into a kind of musical cavalry charge, a tremendously impetuous forward thrust that is interrupted by clashes, conflict and struggle, and even momentarily halted by moments of sheer exhaustion, only to resume its triumphant forward march (listen here). In this movement we are in the thick of the Revolution itself, with all its ebbs and flows, its victories and defeats, its triumphs and its despairs. It is the French Revolution in music.

The second movement is a funeral march – in memory of a hero. It is a massive piece of work, as weighty and solid as granite (listen here). The slow, sad tread of the funeral march is interrupted by a section that recaptures the glories and triumphs of one who has given his life for the revolution (listen here). The central passage creates a massive sound edifice that creates a sensation of unbearable grief, before finally returning to the central theme of the funeral march. This is one of the greatest moments in the music of Beethoven – or any music.

The final movement is in an entirely different spirit. The symphony ends on a note of supreme optimism. After all the defeats, setbacks and disappointments, Beethoven is saying to us: “Yes, my friend, we have suffered a grievous loss, but we must turn the page and open a new chapter. The human spirit is strong enough to rise above all defeats and continue the struggle. And we must learn to laugh at adversity.”

To be continued... here

Footnote:

[1] Beethoven was wrong about the Austrians. Two decades after his death, the Austrian working class and youth rose up in the revolution of 1848.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments