Fighting miners, hotel workers, Machinists sign up for ‘Militant’

BY LOUIS MARTIN

“ This paper needs to get around more,” coal miner Connie Jewell said as he signed up for a subscription to the Militant at the April 1 United Mine Workers union demonstration of more than 6,000 in Charleston, W.Va.

The action was called to protest moves by Patriot Coal to cut thousands of miners off health and pension plans and tear up union contracts. (See article on front page.)

Jewell was one of 27 participants who bought Militant subscriptions at the action. In addition, 46 single copies were sold, showing the interest by coal miners and their supporters in a socialist newsweekly that tells the truth about and backs the struggles of working people.

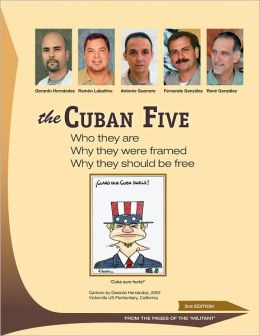

Two books on revolutionary working-class politics were also sold on the buses going to the event, including The Cuban Five: Who They Are, Why They Were Framed, Why They Should Be Free, one of eight books offered at reduced prices with a subscription to the Militant. (See ad below.)

Militant distributors from Seattle had a similar experience when they brought solidarity to the picket lines of members of International Association of Machinists Local 79 on strike against the Belshaw Adamatic Bakery Group in Auburn, Wash., selling seven subscriptions in two visits. The plant manufactures donut equipment. (See article on page 5.)

“It’s important to have a paper like this to see what is happening all over to working people,” said Josephine Ulrich, a shop steward who has worked 25 years at the plant. “I want to show it around. This is what unionization and solidarity is all about.”

On March 30 Militant supporters sold the paper door to door in Seattle and Kent, Wash., reported Edwin Fruit. They talked with working people about the impact of the bosses’ productivity drive, the bank crisis in Cyprus, the cuts in postal service and other political developments of interest to workers.

“I very much liked the fact that the Militant talked about what was happening to us, but I also wanted to support the paper. I also found the international news to be very interesting,” said Brigitte Malenfant when asked why she had decided to renew her subscription.

Malenfant is one of 180 hotel workers who have been on strike since Oct. 28 against the Hôtel des Seigneurs in Saint-Hyacinthe, about 30 miles northeast of Montreal. They are fighting for wage parity with hotel workers in Montreal.

Join the ongoing international effort to increase the circulation of the Militant among working people. You can call the distributors in your region (see directory on page 6) or order a bundle at themilitant@mac.com or (212) 244-4899.

http://www.themilitant.com/2013/7714/771406.html