The birth of the Communist Party of Italy (PCdI) 1921

(FalceMartello) Friday, 13 May 2011

Ninety years ago at the Livorno congress of the Italian Socialist Party a decisive mass split took place, which led to the foundation of the Italian Communist Party. The split came in the wake of the defeat of the Occupation of the Factoriesa few months earlier and marked a clear dividing line between those who understood the need for revolution and those who had adopted a reformist outlook, adapting to the needs of capitalism itself.

The outbreak of the First World War led to the collapse of the Second International. The Socialist Parties belonging to it voted for war credits, betraying the fundamental idea of the International at its birth that called for “the transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war, for the overthrow of capitalism”.

The outbreak of the First World War led to the collapse of the Second International. The Socialist Parties belonging to it voted for war credits, betraying the fundamental idea of the International at its birth that called for “the transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war, for the overthrow of capitalism”.

During those years, left-wing currents had been taking shape inside the Socialist Parties all over Europe. These distinguished themselves from the right wing of these organizations, which had openly supported the war, and from the centrist currents, which had taken an anti-war stance but a very ambiguous one and without adopting Lenin’s call for an unrelenting revolutionary struggle against their own governments and bourgeoisie.

“Neither support nor sabotage”

The Italian Socialist Party (PSI, founded in 1892) adopted a different standpoint from the other European Socialist Parties but without adopting Lenin’s position. The party’s position on the war was declared officially by the party secretary Costantino Lazzari in a conference in May 1915: “We will neither support the war, nor sabotage it”. This position set the PSI apart from the other European Social-Democracies, who had surrendered to their own bourgeoisies, but was not consistent with the principles on which Lenin and Trotsky were laying the foundations of the Third International, which was to mark the passage from the name “Socialist Party” to “Communist Party”, or, in the words of Lenin, “taking off the dirty shirt and putting on a clean one”.

By 1917 the war was having more and more serious effects, leading to a growing radicalisation of the masses as living conditions worsened. Milan and Turin were the cities most affected by mass movements. In Milan in particular, mass movements broke out on Mayday with women in the front line, striking in several factories. The slogan in Turin was “End the war with a general strike”.

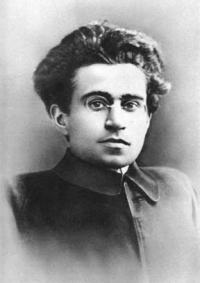

That November the first meeting took place between Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci and four years later they were to become the main leaders of the PCdI that emerged from the split in the PSI at the Livorno congress. During a conference of the maximalists [the majority centrist current of the party], the need was expressed for the first time to expel the right-wing reformists from PSI. This was the tendency nearest to the ideas expressed by the other European Socialist Parties.

Turati, the main leader of this current in Italy, rejected the ideas of Lenin (who saw the war as an extreme expression of the irreconcilable contradictions of capitalism and therefore of the need for a revolutionary solution) and was against the Socialists struggling for power. His ideas were shared by all the right-wing tendencies within the Second International.

The founding ideas of the Third International were supported by the maximalists, a current around Lazzari, the party secretary, and Serrati, editor of the party newspaper. But while they shared the ultimate goals of revolution and the taking of power, they were not clear about the means by which this was to be achieved.

More consistent positions were to be found around Amadeo Bordiga’s faction and Gramsci’s paper Ordine Nuovo, which was based in Turin. Bordiga was a leader of the Socialist party organisation in Naples and one of the main spokesmen for the abstentionist faction which organised around the paper Il Soviet. This faction saw “electoralism” and participation in the bourgeois parliament as a root cause of reformism, a phenomenon that had emerged at the time in the class compromising positions of the party’s parliamentary group). Gramsci’s Ordine Nuovo was forged during the period of rising class struggle in Italy in 1918-19 (in 1919 alone there were 1,871 strikes in agriculture and industry); shops were raided by crowds exasperated by the food situation, while the metalworkers won the eight-hour day.

The two red years – the “biennio rosso”

This was the beginning of the “biennio rosso” (the two red years). In 1919 PSI membership grew from 50,000 to 200,000. From 1918 to 1920 the CGL [General Confederation of Labour, the main trade union confederation linked to the PSI] grew from 250,000 to two million members.Ordine Nuovo was founded in Turin around the figure of Antonio Gramsci, on the first of May 1919, as a “weekly review of socialist culture”. Togliatti, Terracini and Tasca also formed part of the original “ordinovista” nucleus. The editorial board included Alfonso Leonetti (expelled from the PCdI in 1930 together with Tresso and Ravazzoli, who went on to form the first Trotskyist opposition in Italy) and Felice Platone, who were also to be the first editors of L’Unità, founded in 1924 as the party’s official organ. With Ordine Nuovo the Factory Councils movement began to organise – in opposition to the CGL bureaucracy, which was the fundamental base of support for the reformists in the factories – and developed particularly between October 1919 and April 1920, winning over about 150,000 workers to their position.

1919 also saw the First Congress of the Third International, which aimed first of all to clarify the importance and the necessity of setting up soviets and working to spread them, mobilising them in defence of the besieged Russian Revolution. Gramsci saw the Factory Councils as the nearest model to the soviets, where the Bolsheviks had won control, leading the Russian proletariat to victory.

Gramsci and Ordine Nuovo insisted that before taking power, institutions should be created to represent the embryo of the organisations which would become the basis of the future democratic dictatorship of the proletariat.

Meanwhile, Bordiga had a mistaken analysis of the role of the Factory Councils. An article appeared in Il Soviet declaring that the Factory Councils, in creating forms of participation of the workers in the running of enterprises, could become organs of corruption. Bordiga explained that, “the Councils today create problems for the bosses, but tomorrow they will create problems for the revolutionary proletariat” and postponed the issue to some future moment after the taking of power, thus showing that he had not fully understood the lessons of the October Revolution.

Despite these differences in outlook, the Factory Councils in Turin cooperated closely with Bordiga’s abstentionists, on the basis of the common demand for workers’ control of production. The developing class struggle also helped to bring the two tendencies together.

On 25 March 1920 the Turin workers occupied the Fiat factories. The bosses responded with a lockout. A week later the Factory Councils issued a manifesto to the workers and peasants of all Italy for the congress of the Factory Councils.

On 25 March 1920 the Turin workers occupied the Fiat factories. The bosses responded with a lockout. A week later the Factory Councils issued a manifesto to the workers and peasants of all Italy for the congress of the Factory Councils.

The Turin events were an anticipation of the occupation of the factories, which came in September 1920 after four months of fruitless negotiations between the FIOM [metalworkers’ section of the CGL] – whose demands were also supported by all the other workers’ organizations – and the newly formed association of industrialists, who claimed they could not grant even one lira in wage increases. The metalworkers’ union declared that the workers’ starvation wages not only did not allow them to keep up with the cost of living but would not even provide dignified levels of subsistence.

The limits of maximalism

Meanwhile, Bordiga’s abstentionists had met in May 1920, with Gramsci taking part as an observer. In that meeting it was proposed to create a communist faction within the Socialist Party, of which they would all be members.

One of the questions on which the faction had to adopt a position was on the experience of the occupation of the factories. This movement was eventually to be defeated thanks to a negotiated agreement with the bosses, strongly advocated by the CGL (led by the right wing of the PSI), that dashed the hopes of a transformation of society that had been raised by the embryonic form of workers’ control that had come into being. Instead of a revolutionary coming to power of the working class, the union leaders settled for an increase in wages, together with so-called workers’ “co-management” in the running of production.

It has to be said that the boycott of the occupied factories movement by the CGL leaders (which saw the Socialist Party leadership, who at least in words were to the left of the CGL, completely unwilling to offer a lead) was successful also because Gramsci, while placing great emphasis on the situation of the Factory Councils, did not pay enough attention to building a centralized political leadership able to lead the workers’ movement in the taking of power, to replace the completely paralysed leadership of the PSI. The delay in building a communist current within the party on a national level was to have damaging effects that were revealed very soon in the fact that the communist split from the PSI only managed to take a minority of the membership, albeit a sizeable one.

The analysis of the occupied factories movement opened up a painful discussion on the left and with it the recognition of a historical necessity that could no longer be avoided. The main bone of contention concerned the revolutionary perspectives for Italy. At the birth of the Third International in 1919, Lenin and Trotsky had placed their greatest hopes on Germany and Italy.

Bordiga and Gramsci concentrated their efforts on the inevitability of a break with the PSI, a party which even during the occupation of the factories had led demonstrations with the slogan “peasants and soldiers, come over to the side of the workers because the day of freedom and justice is near” but then in practice, at the crucial moment, had given in to the CGL leadership’s boycott.Although the PSI had formally accepted the 21 points of the manifesto of the Third International [i.e. the basic conditions that all parties joining the Third International had to abide by], and had joined the new International, the test of events showed that the Party was still locked within the historical limits of the Second International.

Lenin’s opinion of the Italian situation was crystal clear: the occupation of the factories had represented a golden opportunity for the taking of power by the working class; now it was of the greatest urgency to put at the top of the agenda a break with the counter-revolutionaries in the Socialist Party leadership.

Lenin was still confident of being able to win over Serrati and felt at that time that the creation of the Communist Party could come about by getting rid of the reformist wing. At the second international congress he had recommended the expulsion of Turati from the party to establish a clear identity of the revolutionary wing, which could then seek an alliance with him within the labour movement, applying thus the united front tactic to win over any remaining supporters he may have had. Gramsci was to become a convinced supporter of this tactic, but at the same time did not fail to emphasise the historical necessity of the split, in order to build a completely different leadership of the working class from the one represented by the Socialists.

The communist faction was unified in October 1920. Bordiga had renounced his abstentionist prejudices (a position that had earned him more than one criticism from Lenin, who had specifically written Left-wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder as a basis for the works of the second congress of the Communist International) and had accepted the working out of a common platform with Gramsci.

Bordiga was the organiser and main source of inspiration within the communist faction, with the great authority he enjoyed among the youth wing of the PSI, the FGSI (the Italian Socialist Youth Federation) which went over en bloc to the communist split-off. Gramsci and the Turin group around Ordine Nuovo, even though it had come into being within the University of Turin, as Togliatti admitted, developed the work in the factories that was to provide the Communist Party with its first groups of genuine workers.

The Livorno split

The conference held by the Communist faction at Imola (near Bologna) in November 1920 prepared the ground for what was to become the Livorno split. Bordiga refused any suggestion of an opening towards Serrati. Also Gramsci had made up his mind by that time. The Communist Party was to be formed under Bordiga’s leadership, while Gramsci addressed Serrati in no uncertain terms during a meeting of the Turin Socialist Party branch: “Thirty thousand communists were enough to make a revolution in Russia because that party was homogeneous and knew what it wanted!” When the clash between the Turin editors of Avanti and Serrati led to the suppression of the Turin edition, the executive of the Communist International welcomed the editors of the Ordine Nuovo, which became the daily paper founded by the communists, depicting Turin as the new Petrograd.Lenin now practically abandoned any hopes he may have had of winning Serrati to the Communist Party that was about to be born. The author of the April Theses, which had given a decisive turn to the Russian revolution, saw the communist faction as the only serious basis of support for the International in Italy.

The congress of the PSI at Livorno, held on 19 January 1921, exactly two years after the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, opened with the die already cast with everyone having taken a decision: Gramsci and Bordiga proclaimed the communist split but Serrati did not follow them.

The delegate from the Communist International supported the communist faction and declared himself for the expulsion from the Comintern of those who voted for the maximalists’ motion. When he was faced with hesitation by Paul Levi (leader of the German Communist Party), who had tried up to the last moment to avoid the break with Serrati by proposing that Turati should not be expelled immediately, he sent a telegram to Moscow asking how to proceed and the clear reply arrived to go for a break with Serrati.

The official results of the congress were: 98,000 votes for the maximalists, 58,000 for the communist faction and 15,000 for the reformists. Lenin pointed out that Serrati had preferred to remain with 15,000 reformists rather than go with the 60,000 communists.

The split was proclaimed on the morning of 21 January with a declaration read out by Bordiga:

“…the communist faction declares that the majority of the congress, by its vote, has placed itself outside the Communist International. The delegates who voted for the motion of the communist faction should abandon the hall; they are convened at the San Marco theatre to discuss the formation of the Communist Party, the Italian section o the Third International. Signed by the assembly of the delegates of the communist abstentionist faction meeting in Livorno on 21 January 1921”.

The declaration went on to say:

“Considering that the faction was formed to solve the historic problem of the formation of the Communist Party in Italy, through the struggle against opportunist, reformist tendencies; recognising that this problem has been solved by the outcome of the Livorno congress, by stating that the question of the parliamentary tactics of the communists, as has been faced and sustained in the international arena by the faction, was a critical contribution which maintains its validity in the elaboration of communist thought and method, and is to be considered answered by the deliberations of the second congress of the Communist International; stating that in the Communist Party the presence of autonomous factions is not allowed, but there must be the strictest homogeneity and discipline, it decides the faction is hereby dissolved”.

The founding declaration of the PCd’I (Communist Party of Italy) called for the dictatorship of the proletariat, to be exercised through the system of Councils of workers and peasants.

The first years of the life of the party were affected by the effects of the 1920 defeat of the occupied factories movement and the beginning of the fascist dictatorship, an event that was to seriously weaken the forces of all the workers’ organisations. The Third Congress of the Communist International had already analysed a slowing down in the revolutionary developments internationally, with a slower tempo in the development of the objective situation. This also brought about a debate, with Gramsci and Bordiga in disagreement over the tactic to be adopted towards the PSI, the former moving towards Lenin’s position of the United Front, while the latter adopted an ultra-left sectarian position, which further contributed to weakening of the left as a whole in the face of the rise of fascist reaction.

With the rise of fascism, however, the PCd’I soon had to go underground and was forced to adopt measures typical of clandestine conditions, of absolute discipline, of subordination of the single activist to the whole, which were already referred to in many of Gramsci’s and Bordiga’s writings of the previous years and which highlighted first and foremost the need to build the political organisation of the proletariat that the revolution required, with absolute discipline to a revolutionary centre and an unconditional revolutionary unity.

The words of Gramsci in L'Ordine Nuovo of March 15, 1924, graphically depict the situation:

“the need was thus starkly posed, in an extremely exasperated form, in a life and death situation, of fusing our cells with the very blood of the most devoted activists; we had to transform, in the very act of their formation, of their enrolment, our detachments in the guerrilla war, of the most atrocious and difficult guerrilla war that the working class has ever had to fight. However, we succeeded; the party was formed and formed strongly: it is a phalanx of steel…”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments