EP Thompson: the unconventional historian

The Making of the English Working Class is 50 this year, yet it is still widely revered as a canonical work of social history

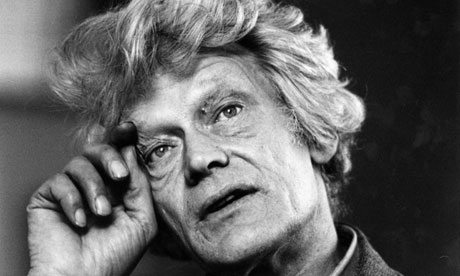

EP Thompson ... intellectual figurehead. Photograph: John Hodder

EP Thompson ... intellectual figurehead. Photograph: John Hodder

Fifty years ago, an obscure historian working in the extra-mural department at the University of Leeds delivered a manuscript, overdue and over-length, to Victor Gollancz – a publishing house then specialising in socialist and internationalist non-fiction. No one could have foreseen the book's reception. EP Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class became a runaway commercial and critical success. The demand for this 800-page doorstop was nothing short of remarkable. In 1968, Pelican Books bought the rights to The Making and published a revised version as the 1,000th book on their list. In less than a decade, it had gone through a further five reprints. Fifty years on, it is still in print, widely revered as a canonical work of social history.

It was not Thompson's first book. A history of William Morris had appeared in 1955, and had been met with the indifference that is the fate of most academic monographs. After The Making came Whigs & Hunters, a book on the Black Acts – the notorious Georgian legislation that criminalised not only the killing of deer, but also any suspicious activity that might hint at the intention to kill deer. This was followed by a series of colourful essays on diverse themes, including time and industrial capitalism, food riots, and wife sales (yes, in the 18th century men really did take their wives to market and "sell" them). Time and again, Thompson proved himself capable of taking on new topics and revisiting old ones in new ways, creating a body of work that was original and hugely influential.

And yet Thompson was never a conventional historian. His many years at Leeds were spent not in the history department, but in adult education. His tenure at the newly created University of Warwick was brief: he resigned just six years after taking up the post, disgusted at the commercial turn it was taking. Ever the man of letters, his resignation was accompanied by a lengthy pamphlet outlining his intellectual objections. The rest of his life was devoted to a range of political causes. Thompson was an active member of the Communist party in the 40s and 50s, and founder of the Communist Party Historians Group in 1946. He was part of the mass exodus from the party in the 1950s following the Soviet invasion of Hungary, but remained closely allied with a range of leftwing movements. By the end of the 1970s, Thompson was playing a key role, as both tireless organiser and intellectual figurehead, in the nascent peace movement, a cause to which he remained devoted until his death in 1993. It was a life of activism no less than of scholarship.

But towering above it all remains The Making, with its preface so memorably declaring the book's intention "to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the 'obsolete' hand-loom weaver, the 'Utopian' artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity". The book's mythic status should not distract us from the raw originality of the work. In 1963, weavers and artisans were not the stuff of history books. Pioneering social historians had been studying working people since the early 20th century, but the focus remained squarely on the tangible, the measurable, the "significant" – wages, living conditions, unions, strikes, Chartists. Thompson touched on the trade unions and the real wage, of course, but most of his book was devoted to something that he referred to as "experience". Through a patient and extensive examination of local as well as national archives, Thompson had uncovered details about workshop customs and rituals, failed conspiracies, threatening letters, popular songs, and union club cards. He took what others had regarded as scraps from the archive and interrogated them for what they told us about the beliefs and aims of those who were not on the winning side. Here, then, was a book that rambled over aspects of human experience that had never before had their historian. And the timing of its appearance could scarcely have been more fortunate. The 1960s saw unprecedented upheaval and expansion in the university sector, with the creation of new universities filled with lecturers and students whose families had not traditionally had access to the privileged world of higher education. Little wonder, then, that so many felt a natural affinity with Thompson's outsiders and underdogs.

And there was something more. Running through The Making was a searing anger about economic exploitation and a robust commentary on his capitalist times. Thompson rejected the notion that capitalism was inherently superior to the alternative model of economic organisation it replaced. He refused to accept that artisans had become obsolete, or that their distress was a painful but necessary adjustment to the market economy. It was an argument that resonated widely in the 1960s, when Marxist intellectuals could still believe that a realistic alternative to capitalism existed, could still argue that "true" Marxism hadn't been tried properly.

Appearing in the heyday of Marxist scholarship, The Making's political framework lay at the heart of the book's success. Perhaps its greatest achievement, however, is how it has managed to weather Marxism's subsequent fall from academic grace. By the 1980s, Marxist history no longer held a significant place in academic history departments. It has been on the defensive ever since. Surveying the literary spat between Thompson and the Polish philosopher, Leszek Kołakowski – who, after years of living under Communism, had had the temerity to desert the Marxist banner – Tony Judt observed: "No one who reads it will ever take EP Thompson seriously again." And yet we do still take Thompson seriously. More than any of his books, The Making continues to delight and inspire new readers. Of course, Thompson's scholarship was partial and driven by his politics. But the originality, vigour and iconoclasm of his book make certain that it will endure.

• Emma Griffin's Liberty's Dawn: A People's History of the Industrial Revolution will be published by Yale later this month.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/mar/06/ep-thompson-unconventional-historian

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments