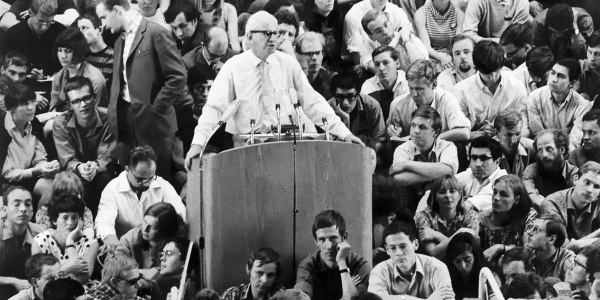

Marcuse's embrace of the student as revolutionary briefly made him a celebrity on campuses rocked by protests, like the Free U. of Berlin in 1967.

Occupy This: Is It Comeback Time for Herbert Marcuse?

"At the end of every concrete philosophy stands the public act."

—Marcuse

Bless the American university, that exemplar of pluralism. Was it a playful University of Pennsylvania scheduler who managed to assign to the same all-purpose Houston Hall over a few days in October both the annual good-vibes Penn Family Weekend and "Critical Refusals: The International Herbert Marcuse Society's Fourth Biennial Conference"?

Not a few Penn dads and moms headed to the first event after parking their oversized SUV's near hotel rooms going for sums that might reinvigorate Haiti. (Even the modestly accoutered Sheraton University City Hotel offered a "special rate" of only $309 a night.) On the Friday, options included the session "Caring From Afar: Helping Your Child Succeed at Penn," or drop-in "Classes With Your Student." Everyone from the LGBT Center to the Wharton School to the Leonard A. Lauder Career Center threw an Open House, and other offerings included facilities tours, a "Conversation With President Amy Gutmann," comedy and musical performances, and opportunities to make family videos and learn the latest Google technology.

Then again, if there had been a mention in the Family Weekend material that Marcuse mania was taking place a few yards away, parents might have wandered toward Bodek Lounge: a capacious meeting space filled with adults their own age in flannel shirts and mussy gray hair rather than J. Crew and sharp haircuts, as well as an impressive group of young folks castable in next year's sure-thing Hollywood film-ploitation of Occupy Wall Street (Michael Douglas as Mayor Bloomberg?). Bodek served as weekend home base for admirers, scholars, and ex-students of Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), the Frankfurt School philosopher who, in the backhanded language of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "endured a brief moment of notoriety in the 1960s, when his best-known book, One-Dimensional Man (1964), was taken up by the mass media as the bible of the student revolts which shook most Western countries in that decade."

Had Penn parents popped in on the scores of Marcuse sessions—they included 1960s activist Angela Davis's command performance in standing-room-only Irvine Auditorium—they'd have heard some contrapuntal, un-Whartonish intellectual music.

Such as leading Marcuse scholar Douglas Kellner of UCLA declaring that "we can use the word 'revolution' again for the first time in many years," and that Ronald Reagan was himself "one-dimensional man." They'd have heard indefatigable conference organizer Andrew Lamas, a lecturer in urban studies at Penn, welcome the passionately supportive crowd at Davis's talk by announcing that he would not welcome them to "the University of Pennsylvania," which was often "destructive toward workers," but to "the People's University that we need, and that we struggle to create." They'd have witnessed Davis herself make clear that she still considered it a "privilege" to have been Marcuse's student and that it is her obligation to champion "the 21st-century relevance of Herbert Marcuse's work."

What better place than a wealthy Ivy League university for the 1 percent and the 99 percent, or the 17 percent and the 83 percent—however you like to slice your fellow Americans—to face the big issue as Occupiers find their successes slipping away before mayoral eviction actions? Can the movement seize on a convincing philosophical rationale and political strategy, or is it fated to fade like the Summer of Love, whenever that was? The Marcuse conference, which drew hundreds of participants and listeners, echoed often with laments over the failure of 60s protest movements to achieve their goals. It also posed a timely possibility. Might Marcuse, whose calls for resistance to and overthrow of capitalism inspired Davis, German radical Rudi Dutschke, French 68ers, and many more, remain a relevant source for social action and philosophical uplift? Even in an era when young Americans care more about grabbing the hottest gadget they can get their hands on than joining hands in a public place?

A Berliner who originally hoped "to combine existentialism and Marxism" under the philosophical aegis of Martin Heidegger, his Freiburg habilitation thesis adviser, Marcuse came to reject the "false concreteness" of Heidegger's philosophy and fled Germany in 1932, shortly before Hitler came to power. He joined the Institute for Social Research, the German think tank (better known as the Frankfurt School) under the direction of Max Horkheimer that became the first in Europe to bring a Marxist approach to social theory. As it relocated from Frankfurt to Geneva, Paris, and New York, Marcuse published significant essays in its journal.

From 1942 to 1951, Marcuse worked—surprisingly, to some later readers, for a German Marxist who became one of America's foremost radicals—for the U.S. government: the Office of War Information, then the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA), and finally the State Department. At OWI, his tasks included analyzing how best to present Nazism to Americans and turn the German public against fascism. At OSS, Marcuse became the leading expert on Germany, helping to distinguish Nazi and anti-Nazi organizations in Germany and to draft a civil-affairs handbook that would be used in de-Nazification. (One Marcuse scholar has claimed that Marcuse drafted the order that formally abolished the Nazi Party after the war, a claim Kellner describes as "an exaggeration.") From 1945 to 1951, Marcuse served as head of the State Department's Central European Bureau.

Marcuse's U.S.-government work shouldn't surprise given that he found the emancipatory Hegelianism in which he believed at odds with German fascism. Kellner, in his introduction to Technology, War and Fascism (Routledge, 1998), Volume 1 of Marcuse's collected papers in English, cites a pointed Marcuse line from an early-1940s essay: "Under the terror that now threatens the world the ideal constricts itself to one single and at the same time common issue. Faced with fascist barbarism, everyone knows what freedom means."

Kellner also shares a pungent observation by historian and activist H. Stuart Hughes: how "deliciously incongruous" it was "that at the end of the 1940s, with an official purge of real or suspected leftists in full swing, the State Department's leading authority on Central Europe should have been a revolutionary socialist who hated the cold war and all its works." Although Marcuse's presence helped the postwar rebuilding of Germany to include progressive political elements, Marcuse also criticized the return to power in Germany of officials with National Socialist ties. He saw the developing cold war as a case of two systems—Soviet Communism and advanced Western capitalism—moving toward tightened control of their societies, if not equal totalitarianism.

In the early 1950s, Marcuse took research posts at the Russian institutes of Columbia and Harvard before teaching philosophy from 1954 to 1965 at Brandeis University. Those years produced his three most important books: Eros and Civilization (1955), Soviet Marxism (1958), and One-Dimensional Man. From 1965 to 1970, Marcuse taught at the University of California at San Diego, where he became famous as the intellectual mentor of the student protest movement. Unlike his Frankfurt School colleagues Adorno and Horkheimer, Marcuse enthusiastically supported student protests. His later works An Essay on Liberation (1969) and The Aesthetic Dimension (1978) cemented that commitment. By the time of his death in Starnberg, Germany, in 1979, he ranked as a major international philosopher, a status that fewer would accord him today.

Marcuse's "one-dimensional society" amounted to an epithet for advanced capitalist society, which Marcuse, like the Italian Marxist thinker Antonio Gramsci, saw as bamboozling (that is, exercising "hegemony" over) workers of every stripe. It did so through a consumer system that met basic needs and provided a false sense of democratic participation as inequalities in wealth and income grew. In that society, Marcuse detected, in the words of Marcuse scholar Charles Reitz, "alienation in the midst of affluence, repression through gratification, and the overstimulation and paralysis of mind." Even in so-called individualistic America, according to Marcuse, individuals lost their critical intelligence amid the avalanche of products and diversions, becoming inauthentic conformists.

Marcuse's ugly and unwieldy term "repressive desublimation" captured a real phenomenon: the erotic identification of consumers with commodities they purchase. Marcuse would not have been fazed by Americans camping out all night to grab the latest gizmos on Black Friday, only to regard them every few minutes with loving adoration once reserved for children. Marcuse noted, in One-Dimensional Man, an earlier version of the phenomenon: "People recognize themselves in their commodities. They find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment."

In light of such behavior, Marcuse abandoned the old Marxist notion that workers would be the vanguard of anticapitalist revolution. Instead, he vaunted the role of students and discriminated-against minorities such as African-Americans. Combined with Marcuse's embrace, in his revisionist, Freudian Eros and Civilization, of liberationist sexuality, the expansion of the play impulse, and the ability of art to build resistance to a highly administered, repressive capitalism—Marcuse believed that beauty leads to freedom—the philosophical package positioned him as an effective guru to 60s radical youth already throwing off antiquated sexual mores. As Richard Wolin aptly put it in Heidegger's Children (2001), Marcuse thought philosophy's "primary aim was the defetishization of false consciousness." His benchmark of social progress remained the "emancipatory ends of Marxism—putting an end to the degradation of the working class at the hands of a commodity-producing society."

Yet even some thinkers who shared Marcuse's critique of capitalism found him philosophically difficult to swallow. In Herbert Marcuse: An Exposition and a Polemic (Viking Press, 1970)—the only "Modern Masters" monograph ever published with such a stinging subtitle—the not-yet-famous Alasdair MacIntyre condemned Marcuse's work as "incantatory and anti-rational, a magical rather than a philosophical use of language." MacIntyre contended that Marcuse's work "does not invite questioning, but suggests that the teacher is delivering truths to the pupil which the pupil has merely to receive. ... Marcuse seldom, if ever, gives us any reason to believe that what he is writing is true ... he never offers evidence in a systematic way."

As the Marcuse conference indicated, however, a philosopher can inspire as much by general bent—by commitment to the idea of theory and practice lived together—as by piecemeal arguments for particular positions. Kellner, in that same introduction to Technology, War and Fascism, argued that Marcuse's years working for the U.S. government made him a more practical strategist than the abstract tone of some of his writings suggests. A thinker, in short, whose fusion of "philosophy, social theory, psychology, and politics" might make him relevant again. The conference raised hopes along that line.

"Ideas don't exist in the abstract," Peter Marcuse, Herbert's son and an emeritus professor of urban planning at Columbia University, commented at "Roundtable 62: Documenting Marcuse Across Four Continents." It ranged over the reception of Marcuse's work in China (where he sold hundreds of thousands of books), the Soviet Union (Raisa Gorbachev admired him), Germany, and Brazil. It also served as an overview of Marcuse's present status because of the presence of several close to the flame, such as Peter himself, Kellner, and Peter-Erwin Jansen, responsible for the German edition of Marcuse's works.

His father's corpus, Peter Marcuse continued, "was a litmus test for what a society's interested in." A publisher in Egypt, he noted, had recently sought to translate Soviet Marxism, observing that his father's work is always in play when there's talk of "an alternative to capitalist society." His father, he thought, would have been excited that his books were being discussed exactly when the Occupy movement was drawing attention, since he always saw his ideas as best understood in the context of "social change."

Jansen agreed that Marcuse insisted on a "right of resistance." He remembered once being present when someone asked Marcuse, "So, Herbert, tell us what we can do to bring about social change." He said Marcuse answered, "You know what to do!," meaning go protest! "If you don't know what to do," Marcuse added, "go to the church."

For Peter Marcuse, the hope was that the "happy coincidence" of the conference and the Occupy movement converging might mean that his father's work could aid the push toward a better society.

"Over the last 20 or 30 years," he remarked, speaking of his father, "Marcuse was totally missing. ... Now Marcuse comes from the outside. That was not the case in the 1960s. He's almost an unknown name."

It was left to Alex Callinicos, Marcuse expert and critical theorist, to speak directly to the young people present at the closing round table, who included a number of Occupy Philadelphia participants: "Don't just get caught up in the euphoria of the moment. What's important is how you go on, what you do next."

That said, the Marcuse scholars themselves preferred to feel, in the conference's large turnout and edgy excitement, the euphoria of the moment. "For those of us who have been doing Marcuse scholarship," remarked Kellner, "this is utopia."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments