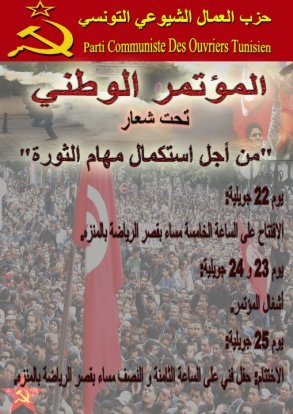

Tunisia: Communist Workers Party holds first legal congress in 25 years

July 23, 2011 — AFP – For the first time in 25 years, the Tunisian Workers’ Communist Party was able to hold a congress. Long banned, the party was legalised after the fall of President Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime.

The Tunisian Communist Workers’ Party (PCOT) held the first session of its first party congress as a legal organisation on July 22 (the congress was held July 22-24 in Tunis). It featured foreign delegates and guests from Europe, Latin America, the Arab world (press reports and releases highlight the presence of Palestinian communists at the meeting in particular). The atmosphere was playful though the attendees did not fill the venue (estimates by those in attendance put the number at between 1700 and 2000 people).

Leader Hammami gave a speech in which he defended the party from accusations of involvement in violence, lobbed indirect attacks against “the forces of regression” (this along with other comments that can be seen as indirect attacks on [the Islamist party] an-Nahda and the transitional authorities, who have accused the PCOT and Islamists of being “extremists” stoking recent unrest)¹, urged party members and followers to register to vote in the coming constituent assembly elections and stressed the need for ongoing efforts to reach the “objectives of the revolution”, which was described as “a revolution of the people not by a coup”. He also praised the role of Tunisian women in the January uprising, saying that Tunisians deserve full political equality due to their long struggle.

[The PCOT has recently faced accusations from the transitional government and others alleging that the party has been subverting the country through demonstrations and rabble rousing that have caused recent violence. The party says the police and agents of the old ruling party, the RCD, have been the source of violence and the PCOT’s leader has called for an independent investigation to establish the time line of events during recent disturbances. Earlier this month, a crowd gathered outside the hall the PCOT planned to hold a meeting, tearing down posters and blocking the meeting from taking place; party leaders blamed the interior ministry and police. Similar incidents have taken place with other political parties; violence between religious activists and secular parties has also taken place.]

The congress began with a moment of silence for Tunisians who died in the uprising, with a performance by musicians playing “The International” and other songs sung by Rym al-Banna (who sang draped in Tunisian and Palestinian flags) and chants from attendees such as (all of these rhyme in Arabic):

خبز حرية كرامة وطنية (!Bread! Freedom! National dignity)

الشعب يريد الثورة من جديد (!The people want a new revolution)

الشعب يريد اسقاط النظام (!The people want the downfall of the regime)

الشعب يريد تحرير فلسطين (!The people want the liberation of Palestine)

July 25, 2011 — During one of the sessions, the party’s leaders (Hamma Hammami and others) considered changing the party’s name to leave out الشيوعي ”Communist”. Various Tunisian commentators have noted that while the party has a strong core and enjoys relatively strong credibility with certain parts of the public the PCOT nevertheless suffers from its identification with communism. Many Tunisians associate communism with obsolescence, authoritarianism and atheism; the last problem is particularly relevant in that it exposes the party to particular attacks when faced with other parties coming from the Islamist tendency and other leftist parties not identified with the same label who are not seen as being hostile to religion. Tunisian news reports noted that the issue came up on the second day of the congress and that no decision was reached as to whether or not to change the party’s name.

This points to something that should be obvious to most observers, and was noted by Issandr El Amrani in a recent interview: most Arab societies are relatively conservative in religious and cultural terms. The PCOT’s unabashed communism and secularism exposes it to two primary lines of attack which some believe put it at a disadvantage: its aggressive secularism (and supposed atheism; its sometimes strategic use of the terms العَلمانية and اللائكي when referring to secularism reflect an awareness of this problem; the former (which is standard Arabic for secularism) sometimes has connotations of atheism while the latter is an Arabisation of laïcité and has certain rhetorical/political advantages in this regard; this issue is discussed at some length by Fouad Zakariyya), which frightens and even angers religious elements, and its association with the “far left” (l’extrême gauche) which is painted by more economically conservative partisans and the transitional government as the source of recent instability, which alienates more middle of the road leftists and social democrats.

Even in a place like Tunisia where laïcité has been the rule and many people consider themselves secular, there is stigma attached to irreligiosity. On the other hand, many Tunisians are left leaning and of those Tunisians who have made up their minds a relatively large proportion have told pollsters they intend to vote for left of centre parties in the upcoming constituent assembly election. Compared to several other parties, the PCOT usually does relatively well but usually comes in after other, more moderate democratic socialist parties, who themselves are outdone by an-Nahdha (whose share is usually between 25% and 30%).

The PCOT’s website and literature describe its attitude toward religion and the relationship between religion and politics in great detail and quite explicitly on topics ranging from secularism and national (Tunisian Arab) identity, the hijab (it is worth noting that one finds hijab clad women at PCOT rallies but that its leadership often appears with members in headscarves), women’s rights and a variety of other topics. Many of them are combative polemics and engage the writings of prominent Tunisian Islamists (including Rachid Ghannouchi) directly while quoting and referencing Lenin. (Some of these will be translated in upcoming posts.) The party’s position on religion is well known, and it fits into the same broad category as most other leftist parties in Tunisian hoping to protect secular principles in the drafting of the new constitution. While many Tunisians are sympathetic on this front even many people who might otherwise be sympathetic to their platform are somewhat put off on this front. The party’s recent communiques have attempted to remind their audiences that the PCOT respects religious freedom and that as communists they are not against religion, per se.

The party is associated with the “far left” and its association with “communism” is well known to alienate more economically moderate Tunisians, especially elements of the middle class less excited about “continuing revolution” and more interested in re-establishing “normalcy”. It has been active in recent protests which have turned violent, and while the PCOT and its allies blame RCD stay behinds and the security forces there are many Tunisians put off by its radicalism. While “social democratic” tendencies go down more smoothly with average Tunisians “communists” face a challenge of overcoming prejudices about their style of rule and the applicability of their ideology to the current political and economic setting. The stigma attached to the PCOT simply for calling themselves “communists” may be as strong if not stronger than their reputation related to secularism. An al-Jazeera Arabic report on the party convention reflected this when quoting journalists whose seemed to be mocking the party’s communist identification.

These supposed handicaps aside, the party benefits from the reputation of its leaders, many of whom were detained or tortured under Ben Ali, and for its active and well-known participation in the January 2011 uprising. It has a strong populist streak. It has a straightforward and popular stance on Palestine and the Arab uprisings. Like most Tunisian parties the PCOT is relatively small, but it has built a relatively strong organisational infrastructure with branches spread out across the country and a very efficient propaganda and communications effort using Facebook and other social media. It has a vibrant youth and student component and older networks built over its many years of clandestine activism (it remains a Leninist organisation after all). Its activists and leaders frequently appeared on al-Jazeera and France 24 during and after the uprising. (Readers may recall seeing Hamma Hammami’s daughter on an al-Jazeera English program focused on young women involved in the uprising identified as the daughter of a prominent opposition figure whose affiliation was not mentioned.) Its political acumen will be put to the test in the open in October.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments