Chairman Mao’s (or Deng Xiaoping’s) Theory of the Three Worlds is a Major Deviation from Marxism-Leninism

Robert Seltzer and Irwin Silber

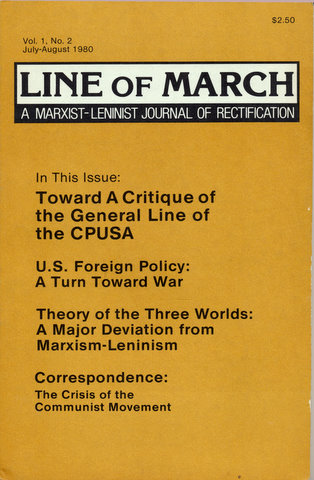

First Published: Line of March, Vol. 1, No. 2, July-August, 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Line of March Note: This article has been developed from a presentation made in May 1979 at a forum sponsored by the Marxist-Leninist Education Project. Robert Seltzer – A member of the Northern California Alliance. Irwin Silber – A member of the Line of March Editorial Board.

* * *

There is no surer sign of ideological and moral collapse than when outrages once deemed beyond the pale of contemplation become commonplace.

Such is the case with the international policies pursued today and over recent years by the Communist Party of China (CPC). It has become obvious that those policies do not represent some momentary lapse or temporary aberration. They are the reflection of a world outlook which has been synthesized as a comprehensive theory explaining all of contemporary politics.

That theory is known as the Theory of the Three Worlds, first advanced in public fashion in 1974 by the man who today is acknowledged to be the moving force and guiding light of the CPC, Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping. Its fullest elaboration was prepared by the Editorial Department of Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily) which published it November 1, 1977. This was subsequently published as a pamphlet under the title Chairman Mao’s Theory of the Differentiation of the Three Worlds Is a Major Contribution to Marxism-Leninism by the Foreign Language Press in Beijing.

Marxist-Leninists have by and large rejected the Theory of the Three Worlds, primarily as a result of the political positions to which it has led. At first, some of those positions seemed simply incongruous, such as China’s refusal to break relations with the Pinochet junta in Chile after the overthrow and murder of Allende, or the deference shown the Shah of Iran for his “firmness” in resisting “Soviet social-imperialism.” Then there was that bizarre parade to Beijing of European and North American fascists, war-mongers, and reactionaries, each of whom was appropriately toasted and hailed for their wisdom and “realism” by the leadership of a party presumably devoted to the cause of proletarian revolution.

Troubling though all of these actions were, they were largely confined to the realm of the symbolic. They did not yet impact the world of politics in a qualitative fashion.

But then came Angola’s Second War of Independence in 1975-76, when China attacked the historically developed and universally recognized vanguard force of the Angolan revolution, the MPLA, and objectively backed the South Africa-supported U.S. puppet phony “liberation” groups. The CPC villified Cuba’s military assistance to the MPLA, gleefully repeated and circulated CIA fabrications about Cuba and the MPLA, supplied diplomatic support and arms to the counterrevolutionaries, and effectively linked up with the general positions advanced by U.S. imperialism.

As the Chinese position on Angola was drawn out in its theoretical aspects, and as its supporters in the U.S. further developed the theoretical underpinnings on which their stand was based, it became increasingly clear that the Theory of the Three Worlds constituted the ideological heart of the matter. In other words, contrary to the parochial views advanced by some fringe “left” opportunist and centrist formations in the U.S. communist movement, the subsequent split in the communist movement did not take place over Angola. In essence, the split took place over the Theory of the Three Worlds, although at the time this theory was not precisely identified as the point of contention and ultimately the line of demarcation. The more political formulation which served the purpose of demarcating a developing Marxist-Leninist trend from “left” opportunism was that U.S. imperialism constituted the principal enemy of the world’s peoples. All who opposed this formulation were either in the “left” opportunist camp or objectively sided with it.

Centerpiece of Strategy

Since Angola, the whole of China’s foreign policy has confirmed that collaboration with U.S. imperialism was not merely a tactical maneuver, but the centerpiece of a strategy which, stemming from a narrow bourgeois nationalist ideological view of the Chinese revolution and its relationship to the world, is now directed primarily at the Soviet Union and its allies.

In short order, the world witnessed China’s praise for the joint French-Belgian adventure in modern gunboat diplomacy in Zaire, Beijing’s constant clamor for the strengthening of NATO, Deng Xiaoping’s criticism of the U.S. for showing weakness in Iran and failing to deal “effectively” with Cuba, the military assault on Vietnam, Chinese military aid to counter-revolutionary forces in Afghanistan long before the Soviet intervention in December 1979, and an ideological torrent directed at the Soviet Union, Vietnam, and Cuba that outdid the propaganda atrocities of the CIA-sponsored media projects aimed at sowing unrest in socialist countries. Today China has effected a tacit political alliance with U.S. imperialism, an alliance which is on the verge of maturing into a full-blown explicit military alliance.

All of these moves have been accompanied by a marked change in China’s view of the international communist movement, highlighted by the CPC’s discovery that socialism has been restored in Yugoslavia and resumption of normal party-to-party relations with the second most ardently revisionist of the western European parties, the Communist Party of Italy.

“National Interest”

There would be no difficulty in making sense of this somewhat dizzying array of events if China were not a socialist country. We expect capitalist countries to act out of “national interest” (meaning the real interests of monopoly capital) without regard to the “principles” which supposedly enlighten their governments. The bourgeoisie’s world outlook is inevitably bound up with a concern for “national” interests because the bourgeoisie requires control of a significant domestic market in order to accumulate capital and therefore has brought into being the modern nation-state as its appropriate political superstructure. The modern bourgeoisie, that is, the monopoly capitalist class, likewise proceeds from concern with “national interest” because “national interest” means the protection of its vast system of export of capital extending throughout the world.

But since China is a socialist country – that is, its mode of production has been socialized and represents the first stage of the communist mode of production – then when its policies reflect a similar concern with perceived ”national interest,” it becomes apparent that ideologically the CPC has sunk into the morass of a profound bourgeois nationalist deviation.

The Theory of the Three Worlds is the concrete theoretical expression of this nationalist deviation.

This point has not yet been sufficiently grasped by Marxist-Leninists who have tended to confine their critique of China’s line to the arena of politics. We have no intention of belittling the importance of the political critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds. In fact, the political critique is indispensable to the overall line struggle since it provides the materialist foundation for the struggle in the realm of theory which must now unfold.

Still, U.S. Marxist-Leninists have been slow to criticize the Theory of the Three Worlds in theoretical terms. We believe there are three main reasons for this:

First, there is the legacy of pragmatism and anti-theoretical prejudice which is all too characteristic of our movement. This heritage, which is distrustful of theory for being too “abstract,” has no confidence in the capacity of theory to explain the real world. From this perspective, the political expressions of a theory provide much more compelling evidence for judging its content. There is, of course, an element of truth in this approach, in the sense that all theory (and a theoretical critique is a part of theory) must sooner or later be tested against concrete reality. But this necessary materialist foundation for theoretical work in general has frequently provided the basis for never elevating politics to that crucial level of abstraction which is the hallmark of theory and on which basis only can generalizations be drawn.

Second, there is a tendency to view the Theory of the Three Worlds too narrowly. This is expressed in the view which sees the Theory of the Three Worlds primarily as a cynical rationalization for the policy of the Chinese government, equivalent, for example, to the Carter Doctrine. This aspect definitely exists, but the Theory of the Three Worlds is more than a policy line at a given moment. It is, in fact, the CPC’s general line for the international communist movement and must be evaluated as such. It is definitely not a tactical line, but a strategic one.

Finally, we must recognize that even though Marxist-Leninists have by and large rejected the Theory of the Three Worlds politically, our movement in varying degrees has been profoundly influenced by the ideological assumptions underlying the Theory. Thus, there still exists a strong tendency to accept the categories used by the Theory of the Three Worlds – such as hegemonism, superpower, and social-imperialism – even among those who have rejected the theory itself.

Need for a Theoretical Critique

The very weaknesses in our movement which have thus far held back the development of a theoretical critique of the Theory indicate some of the compelling reasons why this task must now be undertaken. There are other reasons as well. For one thing, we will not be able to consolidate our line of demarcation with “left” opportunism until we settle accounts with its principal theoretical constructs. Clearly the Theory of the Three Worlds is one such – in some respects perhaps its main theoretical underpinning. For another, our own history as a trend which emerged particularly as the result of a split with ”left” opportunism imposes upon us a special responsibility to take on this theoretical critique, both as our contribution to the revolutionary movement in general and in order to establish firm ideological foundations for our trend. In fact, in a certain sense, we may even be better equipped to take on this task precisely because of our familiarity with the ideological assumptions involved in it.

Finally, the Theory of the Three Worlds is a material force. As implemented by the CPC, it impacts world events in a negative fashion, assisting imperialism in its attempts to suppress revolution and roll back socialism. As taken up by “left” opportunist groups in the U.S., the Theory of the Three Worlds discredits the communist movement, feeds class collaboration and national chauvinism in the working class, and provides a “left” cover for imperialism.

Taking up the theoretical critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds is therefore a compelling political task.

What is the Theory of the Three Worlds?

The CPC invariably ascribes the Theory of the Three Worlds to Mao Zedong, offering in evidence the following statement by Mao, made in the course of a talk with a visiting head of state in February, 1974: “In my view, the United States and the Soviet Union form the first world. Japan, Europe and Canada, the middle section, belong to the second world. We are the third world… The third world has a huge population. With the exception of Japan, Asia belongs to the third world. The whole of Africa belongs to the third world, and Latin America too.” (Cited in People’s Daily pamphlet.)

Mao’s formulation here is quite striking for its total lack of class content as well as for its glaring empiricism. The world is described in the most superficial terms and principally in terms of national formations. This is so glaring that People’s Daily feels obliged to note that, “In appearance, this theory of Chairman Mao’s seems to involve only relations between countries and between nations in the present-day world.” However, says People’s Daily, the Theory does not eliminate the question of class struggle at all because, quoting Mao, “In the final analysis, national struggle is a matter of class struggle”; and, by extension, “The same holds true of relations between countries.”

Such rhetorical sleight of hand speaks volumes concerning the lack of theoretical rigor which has been characteristic of the CPC’s general line ever since 1963 and which has become even more notorious since the triumph of that paragon of pragmatism, Deng Xiaoping. Of course, in the final analysis, national struggle is a matter of class struggle. In the final analysis, every major political and ideological struggle in the world is a matter of class struggle. Apparently the present crop of CPC theoreticians has such contempt for theory that they believe the rest of the world, including the Marxist-Leninists, will view such absurd generalities as a profound insight that will effectively refute those who still fail to find the class content in Mao’s somewhat less-than-awe-inspiring words.

This quotation from Mao also raises the question of the extent to which the Theory of the Three Worlds is really his and the extent to which Deng Xiaoping has fashioned a rather elaborate theory out of some fairly skeletal remarks. Of course, in terms of the Theory’s validity, Mao’s role in formulating it is irrelevant. Nor is it our intention to suggest that all was well with China’s foreign policy until Deng came along to corrupt it. In our view, Mao remains responsible for the nationalist deviation which provides the ideological underpinning for the Theory of the Three Worlds no matter how little or how much he had to do with its actual formulation.

The question of Mao’s role is important, however, when we begin to take into account a body of closely related phenomena. The Theory of the Three Worlds was first advanced publicly in 1974 by Deng Xiaoping before the downfall of the Gang of Four. It was advanced in a period when Deng had been restored to office but when his grip on power was not secure. The Theory next appears in print in 1977 after the Gang of Four has been deposed and when Deng is beginning to surface again publicly. In 1980, with Deng at the height of his power, we are informed that the Theory has been reaffirmed by the CPC.

Reversal of Positions

And yet, during this same period there has been a massive reversal of positions and lines largely associated with Mao. So far, this has been most apparent on “domestic” questions, the centerpiece of which has been the judgment that the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was by and large a disaster and that the treatment of former Chinese President Liu Shaoqi constituted “the biggest frame-up” in the history of the CPC. But in our opinion, an important and insufficiently recognized change has also taken place in China’s international line since the death of Mao, the fall of the Gang of Four and the consolidation of Deng Xiaoping’s power.

The Gang of Four represented an ultra-left, fundamentally anarchist deviation within the CPC, although it was shaped by an even more pervasive and all-sided nationalist deviation. On international questions, this anarcho/nationalist view was manifest in a strong xenophobic current which stressed China’s “self-reliance” and actually tried to ward China off from the rest of the world. This tendency’s view of capitalist restoration in the USSR was based primarily on an anarchist concept of socialism, but the Gang of Four was likewise extremely dubious on the advisability of forging closer ties with the U.S. The People’s Daily itself notes that the Gang of Four “opposed China’s effort to unite with all forces that can be united, and opposed our dealing blows at the most dangerous enemy. They vainly tried to sabotage the building of an international united front against hegemonism and disrupt China’s anti-hegemonist struggle, doing Soviet social-imperialism a good turn.”

There is, in addition, a large body of political evidence to indicate that a qualitative change has taken place in China’s international line since the death of Mao, as demonstrated by the break with Albania and the split in the “left” opportunist camp internationally.

Perhaps the most telling indication of the change was the shift in China’s informal summation of the world situation. In 1974, the CPC’s position was that “The world is in great disorder – and this is a good thing!” In 1980, a fair statement of the CPC’s overview would be that “The world is in great disorder – and this is a bad thing!”

Anarchist Deviation

The earlier statement, while clearly subject to several interpretations, would be thoroughly consistent with the outlook of the anarchist deviation represented by the Gang of Four. It is of a piece with such “absolutes” as “It’s right to rebel” and other semi-anarchist formulations which enjoyed currency during the Cultural Revolution. The view that disorder is a good thing in its own right fails to distinguish between revolution and counter-revolution, consciousness and spontaneity. It is an expression of the anarchist idealization of chaos as the only just social order. The political basis for Marxist-Leninists uniting with this view consisted in the fact that modern revisionism, in fetishizing peaceful coexistence, had looked askance at the revolutionary upheaval in the world, seeing it more as a danger than the source for optimism in the struggle against imperialism. Nevertheless, it was undoubtedly a sign of the ideological underdevelopment of the Marxist-Leninists that they took up this formulation in an uncritical fashion.

The present view of the CPC, as in Deng Xiaoping’s oft-quoted comments on “the troubles in Iran” and the CPC’s frequent complaints concerning “unrest” in Latin America and elsewhere, reflects the vision of a world in which any weakening of the imperialist system is seen as objectively aiding “Soviet social-imperialism.” In fact, virtually every revolutionary struggle in the world today – from Southeast Asia to the Middle East to Latin America – is seen as a Soviet plot.

This point concerning the alterations in China’s foreign policy since the death of Mao and the fall of the Gang of Four is important if we are to critique the Theory of the Three Worlds in a thorough and precise fashion. For obviously something of major significance took place in China with the downfall of the Gang of Four and it would be quite remarkable if the changes which have occurred since then had been confined to domestic questions.

Some judicious speculation may be in order here. In the uneasy peace which prevailed within the CPC top leadership for a number of years – represented by the leading roles of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai – was there a tacit division of labor in which the line of the Gang of Four led on internal affairs and the line of Zhou and his followers led on international matters? (In such a division, each faction would exercise a “moderating” influence over the other in their various areas of pre-eminence.)

Such speculation is relevant since it seems certain that the Theory of the Three Worlds is primarily the expression of the Zhou Enlai/Deng Xiaoping faction of the CPC, although when first unveiled it was in the context of a set of assumptions and categories that the anarchist forces found acceptable. So let us look at the theory itself as explicitly put forward by the CPC:

The two imperialist superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, constitute the first world. They have become the biggest international exploiters, oppressors and aggressors and the common enemies of the people of the world, and the rivalry between them is bound to lead to a new world war. The contention for world supremacy between the two hegemonist powers, the menace they pose to the people of all lands and the latter’s resistance to them – this has become the central problem in present-day world politics. The socialist countries, the mainstay of the international proletariat, and the oppressed nations, who are the worst exploited and oppressed and who account for the great majority of the population of the world, together form the third world. They stand in the forefront of the struggle against the two hegemonists and are the main force in the world-wide struggle against imperialism and hegemonism. The developed countries in between the two worlds constitute the second world. They oppress and exploit the oppressed nations and are at the same time controlled and bullied by the superpowers. They have a dual character, and stand in contradiction with both the first and the third worlds. But they are still a force the third world can win over or unite with in the struggle against hegemonism. This theory summarizes the strategic situation concerning the most important class struggle in the contemporary world in which the people of the whole world are one party and the two hegemonist powers the other.”

The 1977 amplification of the Theory contains three significant refinements from the first presentation made by Deng Xiaoping at the United Nations in 1974:

– The original statement maintained the formulation of the united front against imperialism as the principal strategic concept of the period. By 1977, this had become the united front against hegemonism.

– The original statement held that revolution was the main trend in the world; the new statement asserts that increasing unity in the struggle against the two superpowers is the main trend.

– The original assessment that it was possible to prevent world war through revolution was dropped; instead, the CPC now holds that world war is inevitable.

These alterations have a profound ideological and political significance.

“Hegemonism”

The shift from the united front against imperialism to the united front against hegemonism underscores the further consolidation of the nationalist deviation in the CPC. Hegemonism is an essentially classless political term and speaks to the relations between nations regardless of social systems. To the CPC, the fundamental problem of our age is not that imperialism exploits the majority of the human race but that strong powers dominate weak ones.

The change to hegemonism also has a more specific political meaning. Any reading of current Chinese theoretical and political literature indicates that hegemonism is also used as a code word for the Soviet Union. The united front against hegemonism is clearly a call for a united front against the Soviet Union. This was not completely evident in 1977 when the CPC still formally maintained the view that its strategy was directed against “both superpowers.” At that time, the Theory of the Three Worlds held that “The Second World is a force that can be united with in the struggle against hegemonism.” Today, however, the CPC holds that the “other superpower” (the U.S.) is also a force that can be united with in the struggle against hegemonism.

“Main Trend”

The second major alteration–from revolution being “the main trend” to unity against the superpowers being “the main trend” – provides the underpinnings for the all-sided class collaboration now practiced by the CPC. In most cases, the CPC today looks at revolutionary struggle as extremely dangerous for the world since it tends to strengthen the hand of the Soviet Union and weaken the position of U.S. imperialism, its “second world” allies and the neocolonialist guardians of imperialism’s interests in the “third world.” In addition, this alteration makes the principal task of the proletariat in the advanced capitalist countries one of uniting with their own bourgeoisie to oppose the threat of Soviet “aggression.” (Certain “left” opportunist groups in the U.S. have already recognized the logic of this position and are calling for an alliance between the U.S. working class and U.S. imperialism against the Soviet Union.

“War Between Superpowers is Inevitable”

The third major alteration was that war between the superpowers is now inevitable; previously it was held that war could be prevented by the action of revolutionary forces. This is, in many ways, the most dangerous change of all. For closely tied to the CPC’s view that war between the U.S. and USSR is inevitable is the view that the Soviet Union constitutes the chief source of the war danger. This alteration has been directed, in the first place, to the imperialist countries themselves, warning them to prepare for war. Further, by making the present situation analogous to that preceding World War II (hence the references to the Soviet Union being today’s equivalent of Hitler Germany), the CPC is declaring that imperialism’s long-dreamt-for holy war against socialism will be a “just” war which revolutionaries should and will support. Carried to its logical conclusion, the CPC’s position paves the way for endorsing a preemptive nuclear strike by the U.S. against the Soviet Union.

There is something demeaning to the communist movement in even having to critique this line on the assumption that it can somehow be advanced in the name of Marxism-Leninism.

CPC’s General Line in 1963

However, our purpose here is to examine in greater depth the theoretical underpinnings of this political line. To accomplish this, it will be useful to compare the Theory of the Three Worlds with the general line which the CPC proposed to the world communist movement in 1963.

The significance of this comparison rests in the fact that it was the 1963 general line which most all-sidedly summed up the critique of modern revisionism and won for the CPC the respect of many Marxist-Leninists throughout the world. Here is what the CPC itself said in 1963 about the general line it was proposing:

This general line proceeds from the actual world situation taken as a whole and from a class analysis of the fundamental contradictions in the contemporary world, and is directed against the counter-revolutionary global strategy of U.S. imperialism.

This general line is one of forming a broad united front, with the socialist camp and the international proletariat as its nucleus, to oppose the imperialists and reactionaries headed by the U. S.; it is a line of boldly arousing the masses, expanding the revolutionary forces, winning over the middle forces and isolating the reactionary forces.

This general line is one of resolute revolutionary struggle by the people of all countries and of carrying the proletarian world revolution forward to the end; it is the line that most effectively combats imperialism and defends world peace.

If the general line of the international communist movement is one-sidedly reduced to ’peaceful coexistence,’ ’peaceful competition,’ and ’peaceful transition,’ this is. . . to discard the historical mission of proletarian world revolution, and to depart from the revolutionary teachings of Marxism-Leninism. (A Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement.)

Four Main Contradictions

The underpinning of the 1963 line was a reassertion of the four main contradictions in the epoch of proletarian revolution which began with the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. These are:

– the contradiction between the socialist camp and the imperialist camp;

– the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in the capitalist countries;

– the contradiction between the oppressed peoples and nations and imperialism;

– the contradictions among imperialist countries and monopoly capitalist groups.

These contradictions had been previously identified and analyzed by Lenin and Stalin and ever since have been universally accepted by the communist movement. It was also generally recognized that at any given moment one of these four contradictions could emerge as the principal contradiction in the world.

In the period after the Bolshevik Revolution and through the immediate post-World War II period, the general line of the communist movement viewed the contradiction between the socialist camp (which consisted only of the Soviet Union at that time) and the imperialist camp as the principal one, on the ground that defending the first beachhead for socialism in the world objectively constituted the most advanced revolutionary line of the time.

But in 1963, the CPC held that, with the qualitative changes which had taken place in the world with the triumph of a number of socialist revolutions and the intensification of the struggle against colonialism, the principal contradiction in the world had changed. lt was now the oppressed peoples and nations versus imperialism headed by U.S. imperialism. The CPC pointed to the actual struggles then taking place in the world as being in the main struggles against colonialism and neocolonialism and argued that these struggles were the front line of world revolution. The CPSU, on the other hand, argued that the principal contradiction was still between the socialist camp (now headed by the Soviet Union) and the imperialist camp (now headed by the U. S.). This was a nationalist deviation on the part of the CPSU which became a negative force when the CPSU leadership adopted the line of peaceful coexistence as the principal form of struggle to resolve the contradiction between the socialist camp and the imperialist camp. On this point, we believe that the CPC held a correct revolutionary line and the CPSU held an incorrect conciliationist line.

Now, however, let us compare the 1963 CPC line with the Theory of the Three Worlds in relation to certain fundamental Marxist-Leninist concepts and categories.

The Two Camps

The CPC’s 1963 line identifies the contradiction between the socialist camp and the imperialist camp as one of the main contradictions in the world, although it does not characterize it as the principal contradiction. This contradiction is not a subjective determination but emanates from the two distinct modes of production of the respective camps. These modes of production inevitably give rise to different objective “interests” in the outcome of world events.

The Theory of the Three Worlds, on the other hand, completely eliminates the socialist and imperialist camps. The socialist camp is eliminated by declaring that capitalism has been restored in the USSR. From this perspective, the alliance of socialist countries with the Soviet Union is transformed into an antagonistic relationship. Socialist countries which ally themselves with the CPSU politically immediately become puppets and colonies, whereas those which adopt different lines – such as Yugoslavia or Romania – are deemed socialist.

Insofar as the disappearance of the imperialist camp is concerned, the Theory of the Three Worlds does not attempt to prove this statement. The CPC merely asserts it to be so. The only attempt at evidence is the reminder that U.S. imperialism is on the decline.

Bourgeois and Proletarians

One cannot imagine a general line for the communist movement which does not see the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie as a central contradiction of our age. The 1963 general line of the CPC upholds the view that the mortal struggle between these two classes as it unfolds in the developed capitalist countries is a principal force shaping the world.

The Theory of the Three Worlds does not consider this question to have a particular significance at this time. In its concentrated summation of the Theory, the People’s Daily does not even note the existence of class struggle in the developed capitalist countries. At one point, People’s Daily asserts, “we certainly do not mean to write off. . . the internal class contradictions” in the capitalist countries. But it then calls on the proletariat in these countries to ”hold high the banner of national independence, stand in the van of resistance to the threats of aggression from the two superpowers, and especially from Soviet social-imperialism and under certain conditions unite with all who refuse to succumb to superpower manipulation and enslavement.” The Second International, with its call for “defense of the fatherland” and unite with the bourgeoisie, could not have been more forthright.

Neocolonialism

The 1963 general line argues at considerable length that the principal form of anti-imperialist struggle in the world, the actual content of the struggle for national independence, is the struggle against neocolonialism. The CPC argues in the polemic of the time:

The imperialists have certainly not given up colonialism, but have merely adopted a new form, neo-colonialism.... The imperialists have been forced to change their old style of direct colonial rule in some areas and to adopt a new style of colonial rule and exploitation by relying on the agents they have selected and trained.... This neo-colonialism is a more pernicious and sinister form of colonialism. . . . The national liberation movement has entered a new stage. ....In the new stage, the level of political consciousness of the Asian, African and Latin American peoples has risen higher than ever and the revolutionary movement is surging forward with unprecedented intensity. They urgently demand the thorough elimination of the forces of imperialism and its lackeys in their own countries and strive for complete political and economic independence. The primary and most urgent task facing these countries is still the further development of the struggle against imperialism, old and new colonialism, and their lackeys. (From Apologists of Neo-Colonialism, Fourth Comment on the Open Letter of the Central Committee of the CPSU, Oct. 22, 1963.)

By contrast, the Theory of the Three Worlds has virtually abandoned the category of neocolonialism. In laying out the tasks of the “third world,” for instance, the Theory of the Three Worlds says: “The countries and people of the third world constitute the main force combating imperialism, colonialism and hegemonism.” Neocolonialism has disappeared from the CPC’s vocabulary. Where in 1963 the CPC correctly criticized the CPSU for reducing the struggle against colonialism to a struggle merely for formal independence, today the CPC takes the very stand it criticized then. In upholding the “independence” of “third world” countries today, the CPC does not at all differentiate between genuine forces of independence and neocolonialist lackeys. In fact, the most advanced forces in this area – such as Vietnam and Cuba – have become “lackeys” while the puppets of U.S. imperialism are hailed for their defense of independence.

The CPC praises the effort of Zaire’s ruling group of comprador fascists to “solve” the glaring economic problems of that country by making self-serving arrangements with imperialism. Zaire’s efforts at guarding national independence” are viewed as commendable – even though the ”independence” in question is only that small sphere of personal gain acquired by Mobutu and his group through lining their pockets as the pimps of imperialism – while Cuba, Angola, and Vietnam are condemned (and counter-revolutionary movements within them supported) because of their close ties to the Soviet Union.

The CPC’s 1963 line drew out the struggle against exploitation and for national liberation in the colonial and semi-colonial world as the most advanced form through which class contradictions on a world scale were developing in that period. The Theory of the Three Worlds makes the content of these struggles the same as the form: they are struggles for “national sovereignty” and against “hegemonism,” removed from the class essence of those questions.

Class Stand

In summary, the class content of the 1963 general line was quite clear. It had a proletarian class stand toward the main contradictions in the world. And it employed a Marxist-Leninist methodology in analyzing them. On every question, the 1963 line drew out the class content. Concerning the contradiction between the socialist camp and the capitalist camp, it was clear that this was a contradiction based on two distinct modes of production and two antagonistic social systems. The contradiction between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat in the advanced capitalist countries affirmed the revolutionary role of the working class in those countries. The content of the line on national liberation was clearly based on relations between the exploited and the exploiter, not on formal political relations as such. And the rivalries between imperialist countries and monopoly capitalist groupings were acknowledged as endemic to imperialism and, in fact, a strategic reserve of the proletariat.

By contrast, the Theory of the Three Worlds eliminates the socialist and capitalist camps altogether, downplays the significance of the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in the capitalist countries, reduces the national liberation struggles to the objective of “national sovereignty” (whether for the working class, the national bourgeoisie or the comprador bourgeoisie), and attempts to merge the “best” of Karl Kautsky and Winston Churchill by uniting the international bourgeoisie against the Soviet Union and other socialist countries.

In reversing the 1963 general line proposed by the CPC to the world communist movement, the Theory of the Three Worlds offers a completely different perspective on the main contradictions of our epoch. It eliminates certain fundamental Marxist concepts and introduces new ones which reflect the bourgeois nationalist deviation which now dominates the CPC.

A Categorical Critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds

Every scientific discipline utilizes certain categories for the organization of its knowledge. Ultimately, science is dependent on the steadfastness of these categories for its theoretical rigor. The science of biology, for instance, is thoroughly dependent on such categories as mammal, reptile, etc. and cannot tolerate biologists using these categories in a subjective manner.

The same is true of the science of Marxism-Leninism. The fundamental categories of Marxism-Leninism are not arbitrarily arrived at or to be tampered with as any practitioner of the science sees fit. The fundamental categories of Marxism-Leninism are historically derived and represent concentrated summations of social phenomena. These summations are themselves arrived at by employing the methodology of historical materialism and looking at the world from the standpoint of the proletariat. The defense of Marxism-Leninism, therefore, requires a defense of these historically developed categories and a struggle for their use in a consistently rigorous fashion. It also requires a precise examination of the content and use of any new categories.

In advancing our theoretical critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds, therefore, we deem it necessary to examine the basic categories on which the Theory has been built: capitalism, worlds (first, second and third), and hegemonism. A precise examination of these categories as they are used by the Theory of the Three Worlds will reveal the full extent of the CPC’s departure from Marxism-Leninism.

Capitalism

The CPC’s assertion that capitalism has been restored in the Soviet Union is based on a fundamental distortion of the category of capitalism. For the critique of the USSR, advanced by the CPC in a motley fashion but taken up and refined by various followers of the line, has little to do with Marx’s definition of the capitalist mode of production. Features which Marx and all after him have considered essential to capitalism are not to be found in the Soviet Union.

First of all, while the USSR has had severe economic problems, they are not essentially those of capitalist society. Soviet economic activity is regulated by a plan which has eliminated the anarchy of production endemic to capitalist production, a plan which is possible only through the elimination of capitalist competition. Thus cyclical crises of overproduction and under-consumption and the attendant unemployment, inflation, etc. are not present in the USSR.

Second, unemployment, an indispensable feature of capitalism due to the system’s need for a permanent industrial reserve of labor, does not exist in the Soviet Union. Rather, a longstanding labor shortage, compounded by the lack of mobility of the labor force, poses severe problems to Soviet economic planners. Capitalism rarely has a “labor shortage” problem; the freedom of every corporation to relocate its plants and offices, along with the lack of protection for the workers, guarantees that the labor force will be just as mobile as the capitalists require it to be.

Third, labor power is not a commodity in the USSR. Employment is guaranteed as a right of every worker just as it is deemed an obligation of every individual. Trade unions exercise enormous power over working conditions while wages – both individual wages and the “social wage” (the sum total of social services and benefits received by each individual in society) – are established in accordance with centralized planning and not by competition.

Fourth, aside from some black market and other illegal activities, there is no private accumulation of surplus wealth – surplus value in a capitalist society – in the Soviet Union. Therefore, the search for new areas of capital investment potentially more profitable, which is the objective basis for export of capital in capitalist society, is not a component of the Soviet economy. Nevertheless, the Theory of the Three Worlds, based on an analysis that Soviet society looks much like U.S. society, adopts a definition of capitalism that eliminates all objective scientific criteria in determining a mode of production. As a result, the Theory of the Three Worlds not only distorts the category of capitalism, it distorts the category of socialism. For if the economic laws and problems exhibited by the USSR are those of capitalism, then socialism exists only in the imaginations of those blinded by idealist and anarchist visions of a flawless socialism where freedom is the absence of necessity. A greater departure from historical materialism would be hard to find. (For a comprehensive critique of the thesis of capitalist restoration in the USSR, we refer readers to The Myth of Capitalism Reborn: A Marxist Critique of Theories of Capitalist Restoration in the USSR, by Michael Goldfield and Melvin Rothenberg, available through Line of March Publications.)

On a logical basis, from a Marxist point of view, refuting the capitalist restoration thesis, the main theoretical underpinning of the Theory of the Three Worlds, forces the collapse of the Theory. However, we are compelled to deepen the theoretical critique by examining the other categories of the Theory – for two reasons. First, there is the possibility that the CPC will drop the capitalist restoration thesis but maintain the Theory of the Three Worlds. This will in fact remove any semblance of a class perspective from the CPC line and reveal the thoroughness of the nationalist deviation. The line will merely be “Unite with the U.S. against the Soviet Union,” without a shred of justification based on Marxism-Leninism or proletarian internationalism.

Second, in order for us to completely break with the “left” deviation, we need to eradicate the cumulative effect of the Theory of the Three Worlds on our theoretical and political work. This can best be accomplished by deepening the categorical critique which will reveal the anti-Marxist essence of the categories and equip us to critique the political lines and theoretical work of others who continue to use these same categories.

Worlds

It should be recalled from the exposition of the Theory of the Three Worlds that it claims to provide a new analysis of the “political forces” in the world.

However, the concept of political forces is an important objective concept that cannot be defined simply as one may choose. For Marxist-Leninists, the concept of political forces relies on the categories of “social systems,” “nations,” “classes,” and “parties” when examining the international situation.

The concept of “world” arbitrarily merges these distinct categories. Conceptually, this means that different types of social relationships and contradictions are collapsed together, both within “worlds” and between different “worlds.” Naturally, the four contradictions of the epoch “disappear” into the supra-contradictions between “worlds.”

In general, this method of analysis inherently prevents an accurate conception of reality; in particular, it results in a distorted concept of imperialism and the class struggle leading toward socialism.

Because the Theory of the Three Worlds merges categories – and because nations are the basic unit of analysis and the evident building-blocks of the three “worlds” – the doctrine concerning imperialism is objectively revised in three ways: First, imperialism appears to be the policy of nation-states; second, class struggle within countries is mechanically subordinated to struggles to preserve national independence; and third, the qualitative distinction between capitalism and socialism is obliterated.

“The First World.”

This category, which is synonymous with “superpowers,” functions as the cornerstone of the entire Theory of the Three Worlds.

Theoretically and empirically, however, it has absolutely no relation to objective reality. On the one hand, it combines the U.S. and the Soviet Union, countries with qualitatively–and opposed–social systems; and on the other hand, it serves to divide these two countries, respectively, from others that are part of the same social system. In general, the category of “first world” liquidates the fundamental contradiction between capitalism and socialism.

Since the theoretical cornerstone of this category is the thesis that both the U.S. and the Soviet Union are imperialist powers in the Leninist sense, one would think that the foremost exposition of the Theory of the Three Worlds would contain a rigorous demonstration of how the Soviet Union exploits other peoples and nations economically. Instead, we are presented only a few inconclusive examples of how “the Soviet Union buys cheap and sells dear and squeezes enormous profits in the process.” This phenomenon of commodity exchange – many examples of which are extremely dubious just from a factual point of view – is compared with U.S. export of capital as proof that both countries carry on “the same kind of imperialist economic plunder. . . .” Now this is a curious argument for Marxist-Leninists to make, given Lenin’s identification of export of capital as a feature of “exceptional importance” in the imperialist stage of capitalism, as opposed to export of commodities in the competitive stage. Perhaps the CPC believes that the Soviet Union is the only advanced capitalist country in the world in which the motive force for export of capital – i.e., the existence of an “enormous ’surplus of capital’”– has not arisen. Of course, as Lenin pointed out, capital is never “surplus” relative to the social needs of the masses, but rather to the opportunities for it to be invested for an “acceptable” profit. Thus, the absence of Soviet export capital would only make sense if the highest rate of profit in the world existed inside the country, making outside investment superfluous. Even if for some incredible reason this were the actual phenomenon, it would then undermine the CPC’s assertion that the Soviet Union must seek world domination: there would be no economic raison d’etre (and the predictions of Kautsky and Hobson that capitalism didn’t need imperialism would be borne out for the first time in history).

In reality, it is not the illogic of the CPC’s argumentation that is principal here, but the fact that the Soviet Union does not exhibit the features of an imperialist power precisely because it is socialist. Whatever the contradictions in its relations with other countries and the flaws in its foreign policy, the cause is not the quest for profit. (In fact, there is overwhelming empirical evidence that demonstrates this as well, ranging from the generally favorable terms of trade enjoyed by the Soviet Union’s trading partners to the telling fact that the Soviet Union doesn’t own means of production outside its borders.)

In contrast, the engine driving the U. S. into every corner of the world is monopoly capital: it must expand and the material opportunities that allow this must be maintained and extended. All the forces at the command of the state are placed at the service of this imperative, which is reflected in U.S. foreign policy at any particular moment.

The category of “first world,” by merging the socialist Soviet Union and the capitalist U.S., clearly makes impossible any sort of materialist analysis of the real trends in the world.

Ideologically, it denies that socialism, even if led by a revisionist party, is a historically more advanced social system that brings real benefits to the proletariat and the oppressed peoples. Economically, it denies that there is a definite part of the world, the “socialist camp,” where monopoly capital cannot penetrate to control the means of production and determine social development. Politically, it equates U.S. political, economic, and military initiatives to prop up the imperialist empire with Soviet measures to protect its national security and assist, however inconsistently, revolutionary movements and other socialist countries.

“The Second World”

Just as the CPC’s definition of “first world” obscures the distinction between imperialist and socialist countries, so too does its concept of the “second world.” Thus, France and Hungary, Britain and Bulgaria, Canada and Czechoslovakia, West as well as East Germany are now lumped together for one reason and one reason only: each is a relatively developed country, economically standing in a somewhat subordinate relationship to a “superpower.”

Gone from any consideration in this category is the fact that the economic foundation of the countries of Eastern Europe is qualitatively distinct from that of their supposed counterparts in the West. To appreciate the narrow nationalist, anti-Marxist essence of this view one only has to realize that if France were to become a socialist country and establish close ties with the Soviet Union, it would still be in the “second world.” Also gone is any recognition of the fact that all of the “second world” capitalist countries themselves directly exploit peoples and nations in the colonial and neo-colonial world, whereas none of the socialist countries does.

The CPC’s concept of the “second world” ignores the fact that all of the advanced capitalist countries are engaged in fierce economic competition with their “own” superpower, the U.S., whereas the relationship between the socialist countries and “their” supposed “superpower” is not based on competition at all.

Instead, the CPC simply asserts that the “second world” can establish relations of equality and mutual benefit” with the “third world,” and even may be able to “relinquish [its] deep-rooted exploitation of and control over many third world countries.” The CPC qualifies this assertion by saying this realignment will involve sharp struggle, but social revolution is not mentioned.

The essence of this reasoning is that imperialism is reduced to a “preferred policy” of the “second world” countries. In the face of the political threat from the superpowers, they can supposedly invoke a foreign policy that “resolves” the fundamental economic contradictions that exist between themselves and the “third world”; they can “choose” to stop being imperialist.

This notion only holds up if one separates the national aspect of imperialism from its essence as monopoly capital. In other words, the objective relations of exploitation that exist between capital headquartered in the “second world” and the workers and peasants in the oppressed nations of the “third world” must be ignored. This line makes a mockery of the Leninist theory of imperialism as an objective social system rooted in exploitative class relations, and instead reduces imperialism to a subjective state policy.

What this leads to is a Through the Looking Glass world view in which “second world” imperialists intervene in “third world” countries, not to protect their investments, but to protect the masses from even more predatory imperialists. The CPC advertises the French-Belgian military adventure to liquidate the Shaba province rebellion in Zaire as the foremost example of this type of “second world”-“third world” cooperation. Conveniently forgotten are the highly profitable agricultural and mining enterprises in Zaire controlled by European capital, as well as the history of violent European suppressions of anti-imperialist movements in that country, the struggle led by Patrice Lumumba being the most notable example. (Perhaps we are unfair to the CPC. Perhaps they have not “forgotten” this elementary truth at all. Perhaps they merely hold that imperialism’s defense of its investments in such countries objectively defends that country’s national independence. In other words, perhaps imperialism can even play a progressive role in history.)

“The Third World.”

The category “third world” in the Theory of the Three Worlds is the only one that bears some resemblance, if not to Marxist-Leninist theory, at least to popular usage among anti-imperialist forces.

Historically speaking, the legitimacy of “third world” as a Marxist-Leninist category is quite dubious. The term originated in the mid-1950s and was generally meant to describe those forces – particularly in the colonial and semi-colonial world – who, in moving toward independence, were eschewing both the capitalist and socialist paths. In that period, the imperialist countries were considered the “first world” and the socialist countries were considered the “second world.”

Viewed this way, it can be seen that “third world” was not a scientific category reflecting real relations in the world or a mode of production; rather, it was a state of mind that objectively reflected the interests of the national bourgeoisie – such as it was – in the colonial and semi-colonial world. Not wishing to be identified with the imperialist system, the indigenous national bourgeoisie chose not to describe its own aspirations as capitalist (and clearly they could not aspire to have them be socialist). Instead they hit on an ideological stance which attempted to exploit the revolutionary nationalist sentiments of the masses in the oppressed countries.

Because the political aspirations of this sector were objectively anti-imperialist – although not from a proletarian standpoint – they represented a progressive force in the world. Politically speaking, it was correct for proletarian forces to unite with this force. Where the communists failed was in not drawing a clear-cut ideological demarcation with the concept of “third world.”

Possibly this did not seem to be a significant departure from Marxism-Leninism at the time, since the category “third world” largely overlapped with the category of oppressed nations, and during this period the oppressed nations moved to the forefront of the struggle against imperialism, thus lending a revolutionary aspect to traditionally nationalist aspirations.

Nevertheless, “third world” has never been a scientific category of Marxism-Leninism. As an ideological construct, Marxist-Leninists completely reject it. In the CPC’s current usage, “third world” does not rest upon an economic base either, since it embraces “oppressed nations, oppressed countries and socialist countries,” thus completely obliterating the fact that the working class holding state power does not have the same objective long-range interests as the bourgeoisie (however patriotic) holding state power.

In this category, the Theory of the Three Worlds trades upon a self-evident truth: that the struggles of oppressed peoples and nations against imperialism have been the cutting edge of the world struggle against imperialism during most of the post-World War II period. But in the Theory of the Three Worlds as a theory – and also in practice – the CPC has modified this truth qualitatively.

First of all, the Theory completely obliterates the question of neocolonialism. Not only is an “oppressed nation” deemed to be in the “third world,” but the ruling groups of oppressed nations, including those who are the express agents of imperialism, are deemed to be in this “third world.” Thus, such devoted servants of imperialism as Mobutu in Zaire, Pinochet in Chile, Zia in Pakistan, and Marcos in the Philippines are considered “representatives” of the “third world” in councils of nations. In some cases they are even considered paragons of the “third world” because of their exemplary stands against the Soviet Union. Such a political stand is made possible by establishment of “third world” as a classless category.

Second, it is now apparent that the CPC’s litmus test for a “third world” country is not its resistance to imperialism, but is antagonism to the Soviet Union.

The CPC’s use of the category “third world” is much more appropriate to a narrow nationalist or petit-bourgeois or anarchist world outlook than to a Marxist-Leninist world view.

Thus, in People’s Daily we read, the “scientific summing-up of the main experience gained by oppressed nations in their anti-imperialist struggle over the past decades [is that] ’a weak nation can defeat a strong, a small nation can defeat a big... if only they dare to rise in struggle, dare to take up arms and grasp in their own hands the destiny of their country.’[Mao]”

The revolutionary forces in Vietnam, Mozambique, Angola, Nicaragua, et. al., would probably find this summation rather strange, that the essence of their struggle could be defined in terms that exclude the class forces and the political line guiding the revolutionary movement. But this omission is typical in the Theory of the Three Worlds and represents a concession to petit-bourgeois concepts of the national question – “weak” and “small” is good, “strong” and “big” is bad.

Hegemonism

One of the most revealing departures from Marxism-Leninism in the Theory of the Three Worlds is its use of the category “hegemonism.” This category, as used by the CPC, objectively replaces the category of imperialism. The idea that comes through loud and clear is that imperialist powers are bad, not because they maintain monopoly capitalist relations of exploitation, but rather because they seek dominant influence over small countries.

A clarification is required here about “hegemony.” As a concept, it has no class content. Its usefulness as a description of reality depends on the conceptual system in which it is used. For “hegemony” to be meaningful in Marxist-Leninist analysis, one must define it in relation to the nature of the contradiction and the class forces involved. Hegemony can then describe the level of dominance, influence, or authority.

In the Theory of the Three Worlds, the concept of “hegemony” does not merely represent the level of dominance of one or another imperialist power; it takes on a metaphysical life of its own.

Recall that “exclusive world hegemony” is the aim of the “superpowers,” and the strategy to prevent the realization of this objective is termed the “united front against hegemonism.” In order to uphold this formulation, the Theory of the Three Worlds is forced to distort reality and alter the theory of imperialism.

First, it obscures the fact that the U. S. presently holds hegemony over the imperialist system: the post-World War II imperialist alliance has not “disintegrated,” even though there has been a quantitative intensification of the endemic rivalry between the advanced capitalist countries. In fact, the Theory of the Three Worlds deplores this rivalry and urges that it be subordinated to the common interest of the imperialist powers to oppose the Soviet Union. Objectively, the CPC tries to assist in forging a counter-revolutionary alliance, not only against socialism, but against the genuine national liberation struggles of oppressed peoples.

Second, the Theory of the Three Worlds obscures that the principal threat to U.S. hegemony comes, not from the Soviet Union, but from the revolutionary struggles for national liberation and socialism in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The particularity of the period since the end of the Second World War is that a single imperialist power, the U.S., dominates the entire imperialist system to an unprecedented degree. A blow to any part of the system inevitably weakens the system in general and the U.S. in particular. But other imperialist powers do not necessarily benefit, since the practical result of these “blows to the empire” is that territories are often removed from the system. Thus, the main obstacle to continued U.S. hegemony is not the inter-imperialist struggle to redivide the world between competing finance capitalists, but instead the revolutionary struggle to redivide it between capitalism and socialism.

Third, the thrust of the CPC strategy is that the contradiction between “hegemonism” and the peoples of the world is resolved, not by revolution, but by the successful struggle to maintain national independence. From this standpoint, the CPC implies that “equality of nations” is possible under imperialism and that it is not necessary for proletarian forces to lead a struggle for national liberation and socialist construction, since the national struggle against “hegemony” overrides the class struggle against monopoly capital.

The anti-Sovietism at the source of this distortion becomes apparent as successful revolutionary movements in this period invariably develop ties with the Soviet Union for their own self-preservation. In the CPC’s view, this is worse than domination by U.S. imperialism. Thus, revolution must be downplayed.

Fourth, “hegemony” is used to divorce countries in the same social system and sow illusions about the less powerful imperialist powers. Thus, we have “hegemonic imperialism” (the “first world”) and “non-hegemonic” imperialism (the “second world”). The logic is that the imperialism of the “first world” oppresses the imperialism of the “second world.” This in turn produces a “second world” imperialism with its own distinct laws of motion, so that non-hegemonic imperialist powers can actually forge relations of equality and mutual benefit with the “third world.” In essence, a quantitative difference between “stronger” and “weaker” imperialist powers is turned into a qualitative difference between “worlds” by the use of the concept of “hegemony.”

Classless Notions

In sum, what is going on in the Theory of the Three Worlds is that “hegemony” is linked to particular countries and torn out of the context of the imperialist social system. This is equivalent to classless notions such as “power politics,” “spheres of influence,” “nationalism,” etc., that are used by bourgeois ideologists to explain all aspects of international relations between nations. The underlying class relations of imperialism and its character as a social system are neatly dropped from the Theory of the Three Worlds.

The main function of this displacement, of course, is to equate the Soviet Union’s role in the world with that of the U.S. But the advantage of “hegemony” as a concept is that it really doesn’t require a consistent argument that both countries are imperialist in the Leninist sense. It’s enough to point to superficial phenomena of “interference” in the affairs of other countries to claim that the U.S. and the Soviet Union are both following “hegemonist” policies. This has been the logic of CPC propaganda. What we are increasingly presented with is a classless notion of “superpowers” who “seek hegemony” over “small countries.” The question of social system is increasingly irrelevant: “big” and “small,” “strong” and “weak” are the operative concepts.

Should the CPC give up the capitalist restoration thesis, even the thread connecting “hegemonism” to “imperialism” will be severed, and the CPC’s departure from Marxism-Leninism will be total. At that point, the “first world” will embody capitalist and socialist “superpowers,” and it will be even more obvious that the CPC believes the fundamental determinant of a nation’s internal development and role in the world is not its mode of production, but rather the power it has relative to other countries in the world, in particular China.

Surface Credibility

Unfortunately, there is just enough truth in the CPC’s view of the Soviet Union to lend it a measure of surface credibility. For the nationalist deviation operative in the CPSU has indeed led to a stand of great-nation chauvinism toward other socialist countries and a hegemonist policy toward other parties. The essence of this kind of “hegemonism” rests in the serious mishandling by the CPSU of the non-antagonistic contradiction between the “interests” of the USSR and the needs of other socialist countries, communist parties and revolutionary struggles. This stand of the USSR is one of the most conspicuous features of modern revisionism. To equate this deviation by the leading party of a socialist country with the essential class character of imperialism, however, is inexcusable for any party claiming to base itself on Marxism-Leninism.

Communists do not and cannot unite with the CPC’s demagogic and classless use of the category “hegemonism.” Communists are not opposed to seeking hegemony. To the contrary, they advocate and work for the hegemony of Marxism-Leninism over bourgeois ideology, hegemony of the working class over the bourgeoisie, and hegemony of socialism over capitalism.

Conclusion

The Theory of the Three Worlds is a caricature of Marxism-Leninism. It departs from historical materialism in both content and method. It offers a distorted view of reality which, even in its own terms, is incapable of explaining the actual course of events in the real world. And it abandons the fundamental categories of Marxist political economy which are the solid material base for all Marxist analysis.

In terms of class stand, the Theory of the Three Worlds abandons the world outlook of the proletariat in favor of the ideology of the petit-bourgeoisie as expressed in a bourgeois nationalist deviation from Marxism-Leninism. This deviation is also influenced by a significant anarchist strain which has a distinct but related history within the CPC. (In effect, making “hegemonism” the principal target is not qualitatively different from the way in which anarchism makes ”authoritarianism” its principal target.)

In terms of method, the Theory of the Three Worlds is a totally empiricist form of analysis, summing up reality principally by the external appearance of things rather than by their class essence. This is likewise expressed in the pragmatism which is now dominant in the CPC leadership. Deng Xiaoping, notorious for his view that “It makes no difference if a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice,” has graduated to a higher level of pragmatic theory. Today his outlook would more aptly be summarized as “It makes no difference if a country is imperialist or socialist (or a party Marxist or revisionist), so long as it is opposed to the Soviet Union.”

An exploration of the material basis for these ideological deviations is beyond the scope or even the ambition of this article. Such a task is clearly an important one and we trust that others in the communist movement, in the course of interacting with and deepening our own critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds, will also be exploring this question.

While such an examination remains an unfinished task of the critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds, we believe that enough work has already been done to demonstrate both its theoretical bankruptcy in terms of Marxism-Leninism and its blatant opportunism in terms of the class interests of the international proletariat.

At the outset we noted the fact that Marxist-Leninists have by and large rejected the Theory of the Three Worlds politically. However, we believe it important to underscore two political points in particular.

Theory Contributes to War Danger

One is that the Theory of the Three Worlds, operating as a material force in the world through the foreign policy of the People’s Republic of China, makes a qualitative contribution to the very war danger it warns against. Nowhere is the political irresponsibility of the CPC made clearer than in its stand on the danger of war. Theoretically, the Theory of the Three Worlds advances a massive and deliberate distortion of the Leninist theory on the inevitability of war. Lenin demonstrated that in the age of imperialism, world war was the inevitable outcome of the constant attempts by the imperialist countries to redivide the world in accordance with their relative military strengths. From this, the CPC argues that war between the U.S. and the USSR is “inevitable.” But in Marxist-Leninist terms, this view is completely dependent on the unfounded assertion that the USSR is an imperialist country compelled by exactly the same laws of social development as the U.S. Here is the pressing political significance of the capitalist restoration thesis. The irresponsible political stand taken by the CPC, combined with some of the advanced theoretical work on this point recently accomplished by our trend, therefore makes it mandatory that our trend as a whole arrive at a common summation of the question. In the absence of such a summation, it will be extremely difficult to take on the political task of mobilizing the masses against the preparations for war, aggression and counter-revolution which today have become the ever more explicit direction of U.S. foreign policy.

Common Theoretical Summation Is Necessary

Second is that a common theoretical summation of the Theory of the Three Worlds is indispensable for the unity of the Marxist-Leninist trend and the foundation for a general line which can provide the basis for reestablishing a genuine communist party. Such a summation is needed in order to consolidate the line of demarcation with “left” opportunism which can only occur as the political critique of the Theory of the Three Worlds is deepened to embrace its theoretical assumptions and ideological roots. It is needed also to eradicate the vestiges of “left” opportunist thinking which still exist in our trend on international questions and which find expression in a centrist position on outstanding questions of international solidarity – particularly in relation to Vietnam and Afghanistan.

For many in our trend, such a critique and assessment of the Theory of the Three Worlds will be a painful ideological process. It requires surrendering concepts and assumptions developed over the course of time, to a certain extent influenced by the CPC’s prestige in leading the critique of modern revisionism, but also influenced by the anarchist tendencies of the New Left. This has certainly been the case with the authors of this article. But painful or not, it must be done. There can be no halfway house in the struggle against opportunism.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments